Fighting is all about economy of motion.

Every martial arts technique across the world is about finding the shortest possible path to a target, and using leverage to take overwhelming advantage of that target. A judo throw and a boxing slip-and-counter are fundamentally the same; their purpose is to use one’s opponent’s momentum to their disadvantage, by letting them throw themselves over your shoulder, or lean hard into a left hook. Learning to fight is, above all, the study of making things easier for you and harder for your opponent. This is why high-level fighters look like they’re “barely trying” when they dominate inexperienced opponents; their techniques at 10% effort are more effective than their opponent’s at 100%.

This principle is a truism across martial arts, and it applies on all levels of technique: “do more with less energy”. As anyone who has trained will tell you, the baseline techniques of any martial art are about attacking with the whole body rather than just the arm or leg, so that your strikes combine the force of multiple muscle groups instead of just one or two. In grappling, a similar situation: the aim is almost always to create a mismatch, finding an angle where you can create more leverage than your opponent by way of engaging more muscles.

Theoretically, this would mean that a perfect fighter would never need to build strength, because his technique would carry him to success against any opponent. Of course, this is where the concept is taken past its logical end and falls apart. Many have fallen into this mental trap, focusing entirely on technique, with maybe a few light calisthenics as window-dressing. I call it the Ip Man Fantasy – and it is just that, a fantasy.

This may sound harsh, but no one is a perfect fighter, nor will anyone ever be. It is impossible to become so good that you don’t need strength training; it’s an unreachable ideal. I say this because in my experience with teaching martial arts, neglecting this angle is more often a function of ego than anything else. Everybody knows the stereotypical 350lb mall ninja, or the skinnyfat Aikido guru. They place all their faith in technique, with no ability to simply overpower an opponent when that inevitably goes south. Even when their techniques land, they lack stopping power.

But of course, that observation mostly concerns the “traditional martial arts” community. Obviously, MMA fighters and other full-contact competitors know the value of weightlifting. Even then, though, there’s a lot of confusion over what to actually do in the gym for better fight performance. In this article, my aim is to strip down notions about lifting (for fight performance) to their bare minimum. Hopefully, it can then be beneficial to people at any level; providing a barebones framework for the beginner, and some technical information for the advanced fighter.

This piece will be the first entry in a larger series on conditioning for martial arts, and I’ll keep things general for the sake of brevity. I may post some very in-depth information for paid subscribers (i.e. on stretching techniques, training cues, drills I use, etc.) but that is dependent on interest – so let me know if that would be helpful.

Also, I’ll go into a bit of my reasoning before presenting the actual lifts, so if you’re just interested in the tl;dr version, scroll down to “The Lifts”.

On Focus

People tend to get too wrapped up in the vast breadth of exercise information available online. Everybody’s selling a program with some niche proprietary element, and all of them promise that it’s really this “one weird trick!” that will “take you to the next level”. This should be disregarded entirely. Rear delt flies, reverse curls, or any other meme exercises are not going to make you much more effective at fighting.

Similarly, people tend to get wrapped up in what they should specifically focus on – speed, strength, endurance, explosiveness, etc. The answer is all of them. Fighting isn’t Dungeons and Dragons, and putting time into developing one attribute will likely boost the others rather than act to their detriment. You don’t have limited “points” to distribute; only limited time, which demands efficiency.

With that said, if you’re strong but slow, develop speed; if you gas too quickly, develop endurance; if you’re fast but lack power, develop it. Again, no D&D mentality – you shouldn’t ever min-max stats like a videogame character. In fighting, this leads to plateaus in skill, wherein you’ll fight well on your terms against decent opponents, but never advance beyond that.

However, I should clarify that in this article I’m specifically focused on lifting; conditioning and speed/endurance work are separate beasts entirely, and more dependent on the specifics of what you’re training. For example, BJJ fighters will benefit more from shrimping, while kickboxers will benefit more from jumping and burpees. However, all combat sports can benefit from targeted strength training, specifically aimed at building muscular density and central nervous system adaptation to exerting more force with certain muscle groups.

So, with lifting, what should you focus on?

The Posterior Chain

Enter the single most important muscle group in your body. The posterior chain is composed of the muscles that run from the back of your neck to the backs of your heels – traps, lats, glutes, hamstrings, calves, and more. These muscles form the majority of your muscle mass, and much of what has been called “functional strength” – the ability to lift, carry, throw, hold balance, and avoid injury.

Today, these muscles often feel the worst effects of a sedentary lifestyle. Sitting all day malforms your back, and not walking great distances weakens your hamstrings and calves. Tension builds in the upper back, making the trapezius develop knots. Posture today is poorer than ever, due to simultaneous weakness and overstress of the back muscles. Mainstream “lifting culture” doesn’t help, either; the focus on the chest and abs tends to exacerbate these problems.

However, these muscles are perhaps the most critical for fighting. This is counterintuitive, especially in striking; you strike forward, not backwards. Again, though – martial arts are about economy of motion, and creating massive power through technique. And almost all of these techniques are specifically meant to engage the posterior chain.

Consider a teep. The kick shoots straight forward, yes, and it requires use of the quads, hip flexors, and core; but the power comes from violently pushing your hips forward and your shoulders backward, engaging the lower back and glutes. Muay Thai fighters know this, even if it isn’t a common training cue. The muscle engagement on a proper teep is exactly the same as a hang clean, or even a deadlift. See also: side kicks, axe kicks, hook kicks, and anything coming off a spin. All of these kicks gain devastating power from the involvement of the posterior chain, not just the quads or hip flexors. Even roundhouse kicks are usually taught with elements that engage the back to add power.

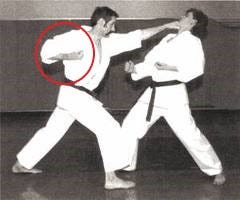

But surely punches derive power from the front of the body? Well, somewhat. While the chest and shoulders are involved, the primary drive still comes from the back. While boxers are taught to launch a cross off the back foot and rotate their shoulders through, it’s not the chest that creates all that explosiveness; in the upper body, it’s the rotation of the opposite shoulder backwards. This is particularly emphasized in short hooks and UFC-style overhands, wherein the opposite shoulder pulling away from the strike actually creates most of the speed and power.

Karate teaches this by emphasizing the chamber in technical work; unfortunately, like many techniques in karate, it’s something that’s taught as dogma without an understanding of why it’s beneficial.

Regarding grappling, the posterior chain is more clearly important. Pulling, holding, bridging, and more are critical elements of wrestling and jiujitsu, and the weight training of Olympic wrestlers or high-level BJJ fighters reflects this. To properly grapple, you need to be able to pick up, throw, hold, and manipulate your opponent, 90% of which is derived from strength in the posterior chain.

On the Shoulders

In my description of the musculature involved in punching, I may have undersold the shoulders a bit to further the point. With that said, they are absolutely critical for any kind of striking power with the hands. While everybody loves to bench, it’s far less critical than most realize for developing a powerful cross or a stiff jab. In fact, benching all the time often creates an overreliance on the chest for punching, something I’ve seen many times with bodybuilder-types starting to fight.

To test my point here, put your hand on the right side of your chest and throw a cross. Your chest is engaged, but by no means the primary driver. Almost all of the power comes from the rotation, your shoulder muscles, and your back. In fact, the chest acts more like a stabilizing muscle than a driver of the punch. The speed and placement comes from your shoulder, backed up by power from the legs and posterior chain.

On the Legs

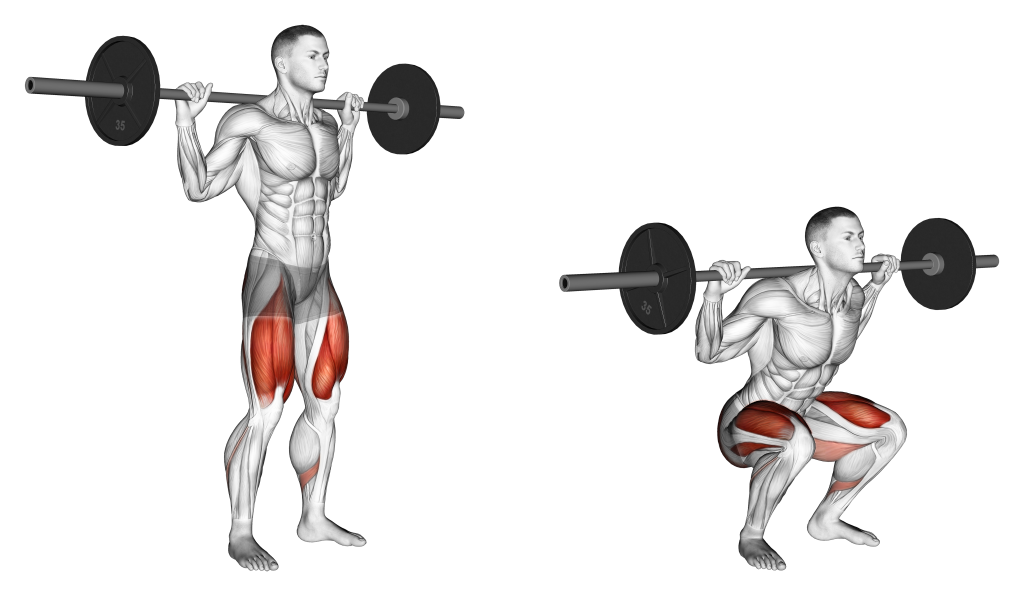

I hardly need to explain why you should be training your legs; the squat is the king of barbell lifts for a reason. It builds strength, explosive power, and stability in your base. While I can talk about posterior chain and shoulder girdle involvement in striking, it should go without saying that all strikes begin with your legs, as does a vast amount of grappling.

Also, squatting causes a release of testosterone and HGH more effectively than any other exercise, which will make you more energetic and make all of your training more effective.

On the Core & Forearms

Of course, the core is extremely important in any kind of athletic activity, particularly fighting. However, short of weighted sit-ups, I consider isolation core work to reside in the realm of calisthenics. For weightlifting, light core exercises should be done to warm up and cool down, but other than that the core is trained separately.

With that said, the core is engaged meaningfully on any compound lift, or any lift that is done standing. Its role as a stabilizer is developed, even when the abdominal muscles are not the focus of the exercise. Similarly, compound lifts are beneficial for developing any and all stabilizing muscles and tissue, all of which are important for martial arts (flexibility, injury-proofing, etc.).

There is also the question of grip strength. In grappling this is a major element, and in striking, it’s critical for wrist stability and injury-proofing, even with hand wraps. It can be trained directly, with a grip strength tool or forearm exercises, or indirectly via barbell lifts.

The Lifts

With all of this in mind, it becomes rather straightforward to choose lifts that will benefit fighting ability. They must work the posterior chain, core, legs, and shoulders; include explosive and strength-based elements; and should favor barbell work (as the barbell requires better stabilization and allows for more weight).

So, a combat sports lifting program would focus almost exclusively on lifts that take the bar from the ground to above your head, and everything in between. These would include:

Power Cleans

Overhead Press

Squat Variations (Low-Bar, High-Bar, Front, Zercher)

And some accessory lifts, aimed at improving those primary lifts:

Deadlift

Hang Clean

Incline Bench

Barbell Bent-Over Row & One-handed Dumbbell Row

Barbell Hip Thrusts

Goblet Squat to OHP

Kettlebell Exercises (Swings, Thrusters, Turkish Get-ups, Clean & Press)

Barbell Lunges

Lat pullovers

Macebell exercises

However, the primary focus should always be on the first three barbell exercises, in that order of importance. I only include the latter list as a way of providing variety, because consistently doing only the same three lifts can get a bit boring, and accessory lifts can help target weak areas and build more well-rounded musculature. Also, if you have any sort of limitation due to injury or available equipment, one of the barbell accessory lifts can be substituted in for the primary lift you can’t do – i.e. deadlift instead of squat, hang clean instead of power clean, incline bench instead of OHP, etc. Of course this isn’t ideal, but it’s still workable. Generally, though, the point of the three primary lifts is that with limited time, one can focus solely on those barbell lifts and still develop everything necessary, supplementing weak areas as needed.

If you’re familiar with the work of Bill Starr, you’ll notice that my primary lifts are very similar to his “big three” for football players, though with the bench press replaced by the overhead press. I don’t prefer the flat bench press for fighting, for reasons explained before, but also for its high injury rate to the shoulders and the fact that it doesn’t involve much balance or stabilization. With that said, when using an adapted version of Starr’s system, his schedule is also best:

Lifting three days a week – day 1 heavy, day 2 light, day 3 medium.

Each day doing the primary exercises in five sets of five, increasing the weight each time.

For better conditioning and more efficient workouts, this should be done alternating between exercises in a circuit style.

This system allows for extremely quick workouts that involve every important muscle group, with plenty of time to work accessory lifts or get back to the mat for conditioning and skill work. It’s simple, extremely effective, and allows the focus to remain on developing fighting skills and fitness.

This system remains simple, yet effectively develops the posterior chain, core, legs, shoulders, and grip – five critically important elements in fighting of all varieties. However, I will reiterate that this is merely meant to supplement conditioning, not replace it. I’ll detail the principles of fight conditioning in another article, but this is already long enough.

Go lift.

As an aside:

While this training method is quite modern (Starr wrote his most important works in the ‘70s), the core concepts are incredibly old. Historically, the primary form of weightlifting for warriors was to lift a stone, sack, animal, etc. from the ground to above the head, or some variation thereof. The Greeks trained like this; so did medieval knights, among many others. The modern Highland Games include historic events used as training benchmarks, and you’ll notice that the weightlifting elements primarily involve the posterior chain, core, shoulders, and grip. Farmer’s carry and sled push-type exercises were also a key element of historic training, and if you have the space/equipment, they’re still great today.

And another aside:

There is also the concept of periodization, which offers a similar benefit though in a different manner. While Starr’s method is best for 99% of the people reading this article (I cannot emphasize that enough), I wanted to include this concept for more experienced lifters, people who have hit a plateau of strength, or those with significant time and knowledge to dedicate to developing their own program.

Described best in K. Black’s Tactical Barbell, this Eastern-bloc training style is unmatched for developing raw strength in major lifts, especially in encouraging central nervous system adaptation to producing great amounts of force and durability in connective tissue under stress. The only weakness of periodization (at least, for our purposes) is that it generally should not be used for explosive lifts – it uses low-rep sets (usually 5x3) with weight near your 1RM, moving up-and-down between 70% and 95% of that number over a six-week period. However, this type of program could easily be integrated with power cleans, hang cleans, etc., as long as you train those after the initial, periodized part of the session. Using Tactical Barbell’s basic program, this would include four exercises. I would choose squat, deadlift, OHP, and barbell row (or incline bench) for best results, which would put you on a 4x/week lifting schedule; power cleans would be trained on the same days, or on the days allotted for other exercises, on a completely separate schedule of progression. Accessory lifts would have to be worked in intelligently to avoid overtraining or injury. Again, this method is far more complicated than the Starr method, but I thought that I’d include it to offer a more bespoke option to those with significant experience. If you’re interested in this program, Tactical Barbell is available here, and also widely available as a PDF online.

David Horne's beginning routine for grip is good for those looking for a grip routine.

Bench press and bicep curls

Drink beer and smoke cigarettes between sets.

Then practice Chuck Liddell overhands in the air to finish up.

Best workout of all time.