This article was originally published on The Dissident Review website — Vol. 1 is live now on Amazon!

Gladiators have retained a unique place in our cultural consciousness, and indeed occupied a unique position in Roman society – they were at once warriors and slaves; entertainers and prisoners; celebrities and criminals.

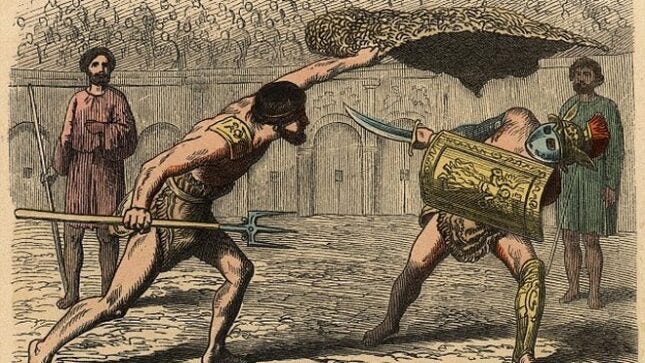

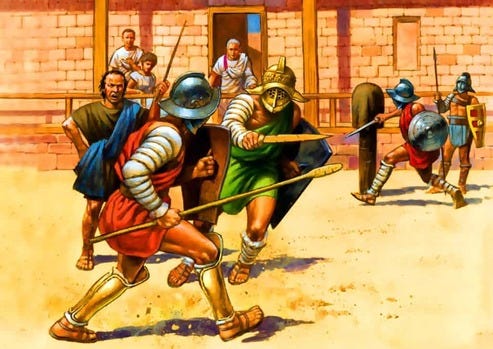

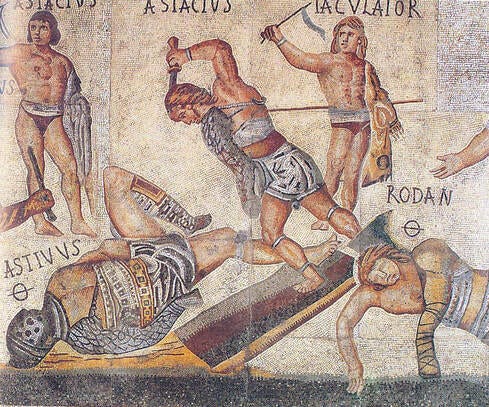

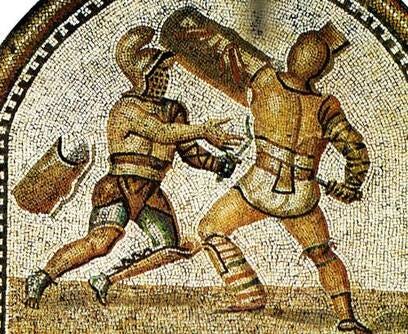

However, our primary-source information on gladiators is quite slim, especially compared to the widespread popularity of the games. The Colosseum could hold 50,000 people at a time, and would regularly pack in that number of spectators. And yet, most of our information comes from a few artistic depictions and the scant archeological record. This fact has led to vast speculation in “reconstructing” the gladiator lifestyle, training, diet, and physique. The film Gladiator (though quite accurate) played up their status as slaves, and gave most of the credit for prowess in combat to prior military training. Spartacus depicted them as lean and sexy, as an explanation for their popularity among Roman women. More recently, the documentary The Game Changers claimed them to be sinewy vegetarian athletes. On the opposing end, certain academics point to depictions of rotund fighters and make the claim that they were overweight, to better absorb slashes, and that they were therefore more so masochistic actors than warriors.

All of these views are in some way too simplistic – and some of them are blatantly wrong. This essay aims to reconstruct gladiator fitness and form, and challenge existing notions on the topic.

For the purposes of reconstructing gladiator physicality, it is important to think of them as athletes above all. Granted, some participants in the games were not athletes, and were simply “thrown to the lions” for the entertainment of the crowd. But these are not the figures we think of today; they were the cannon fodder, the undercard events. The Colosseum’s biggest draws were title fights, so to speak, between experienced and famous gladiators. An entire financial network and social ecosystem grew around gladiator matches, which in many ways mirrors modern boxing or MMA infrastructure. Trainers, promoters, referees, bookies, celebrities, and high-rolling bettors all had a place in the culture surrounding gladiator events. As foreign as Roman bloodsport seems to modern society, it resembled today’s MMA scene in many ways.

A critical element of the gladiator culture was the lanista, who procured, housed, and trained gladiators. These men were slave-owners, yes, but their core role was overseeing the training of fighters. Many were war veterans, former gladiators, or businessmen who employed soldiers and former gladiators for training. The most important part of their skillset was this ability to instruct, not investment or fight promotion. Gladiators, therefore, were professionally trained on a full-time basis, and their day-to-day life was that of an athlete, not merely that of a slave. Hence thinking of them as athletes.

Also, gladiators themselves often entered the ludus (training school) with prior experience. The most successful fighters were prisoners-of-war, who had received prior military training and had seen combat. They were often well-fed, disciplined, and fit soldiers who had happened to meet the wrong end of the Roman legions. Due to their athleticism and experience, they were sent to the Colosseum rather than the mines or other slave-labor projects. These fighters became major investments, and contrary to the common cultural conception, often had long-lasting careers. In fact, only 10-20% of gladiator matches ended in death for a fighter. Great fighters could expect to continue fighting for years, and perhaps eventually be freed for a peaceful retirement.

However, the format of gladiator fights required extremely specific training. Small-scale combat with minimal armor and strange weapons led to a different style of fighting and training than infantry combat. There was also the entertainment factor; gladiators were expected to shock the crowd with their techniques and swagger. Showmanship wasn’t the first priority – winning was – but it certainly played a role.

So, gladiator training had stark differences from typical Roman soldier training. There was no need for group cohesion, marching, or building camps; so, fighters spent all of their time on their fitness and technique. Some of their equipment was very difficult to use, like the Retiarius’ net and trident or the Scissor’s namesake contraption, so a great deal of time would be dedicated to achieving proficiency with this odd weaponry. Different schools employed different methods of training, but the most common “split” was the Tetrad, a relic of Greek athletic culture. This four-day schedule alternated physical effort with rest and technical work.

The Tetrad system:

Day 1: Described as “preparation exercises”, this day included training that would be described today as HIIT (High-Intensity Interval Training) or agility work.

Day 2: This was a full day of all-out effort, meant to test an athlete’s physical limits and push him to the limits of strength and exhaustion.

Day 3: Rest and recovery (more on this later).

Day 4: This day varied in its application, but was usually dedicated to technical skill work.

The fact that gladiators trained on a schedule designed for Olympians furthers the notion that they were athletes above all else. Their minimal armor also necessitated that gladiators were extremely athletic and agile, able to deflect, dodge, and parry attacks. The “grit” factor that typical soldiers needed was less of a priority than extreme technical proficiency and nimbleness.

This also led to an interesting style of training. Gladiators almost surely did some form of calisthenics, though obviously there would be no archeological record of this. They did not directly weight train – dumbbells and rocks designated for weightlifting were in use at this time, yet they haven’t been found at excavations of gladiatorial schools. However, they did practice with wooden weapons built to be double the weight of their metal counterparts. Besides these training weapons, excavations have shown only one piece of true exercise equipment – a narrow post. Much like the medieval practice of training “on the pell”, usually a tree trunk, gladiators trained against a wooden post at the center of the training arena.

This style of static training was both an exercise and a technical tool, much like a boxer’s heavy or double-end bag. The small size of the pole (only a few inches in width) required precision for thrusts and commitment to cuts. This would build technical proficiency, and the heavy weapons used would build what is now called “speed strength”. Additionally, it would build what wrestlers sometimes call “tendon strength”: the shock of hitting an unmoving object with a weapon would build strong connective tissue, especially in the wrist and shoulder.

As anyone who has trained with swords or other hand weapons knows, swinging anything around – and especially striking – is extremely tiring for one’s shoulders and forearms. It builds muscle in those areas rapidly, as each thrust or cut is in effect a low-weight rep, performed over long sets with no true rest. This style of training – low weight/high repetition, with particular stress on the shoulders and forearms – would not build a statuesque physique, as many fanciful depictions tend to show. The chest and back wouldn’t be developed enough to create the necessary shoulder-to-waist ratio, and the leg strength requirements would favor fighters with a more even ratio, though with powerful arms.

To expand on the point of lower-body strength, gladiatorial combat necessitated extremely strong legs. Sword-and-shield work is very stance-oriented, moreso than arts like boxing. Fighters in every such system are usually much lower in their stance than hand-to-hand fighters. When considering this along with the addition of armor, leg strength and mobility becomes fundamental. Almost every depiction of gladiator training shows them in full armor, or close to it. So, gladiators likely had well-developed lower body strength and musculature.

The lower body strength required to fight in armor dispels the notion of skinny, sinewy gladiators, as the weight of armor and weapons would favor larger fighters who could more easily bear the weight and continue moving quickly. Speed strength requires a basis of absolute strength, and a 120 lb. fighter simply does not satisfy that requirement.

Finally, there’s the aspect of cardiovascular endurance. Gladiator fights had no “rounds”, so to speak, and archeologist Wolfgang Neubauer estimates that the average match lasted fifteen to twenty minutes. That’s longer than current UFC fights, without any breaks – and in full armor. The cardiovascular endurance required for such a feat is nothing short of absurd, and this requirement finds few parallels in modern sports. To prepare for this, primary sources make it clear that gladiators sparred constantly in training, alternating between opponents with little rest. Almost every depiction of training in a ludus shows every fighter engaged to an opponent, with the entire scene constantly occupied by combat.

This cardiovascular requirement alone dispels the notion of overfat fighters. However, this notion does contribute an interesting and valid point to the discussion – that gladiators needed some subcutaneous fat in order to not simply die from a small slash to an unarmored area. And, when taken along with their style of exercise, it becomes clear that fighters were likely not “shredded”, and did in fact have some fat – though not to the extent that certain historians say, as it would simply be impractical to lug the extra weight around for a twenty minute deathmatch.

From exercise information alone, in the context of modern sports science, we can paint a picture of what type of fighter was advantageous in the arena. The best gladiators would be larger than average, with some fat, though not large enough to be slowed down by their weight. Their style of fighting favored powerful arms and shoulders, with a strong base of lower-body strength to deal with armor.

This differed between types of gladiators – for example, a Retiarius fighter would likely be smaller and faster than a Murmillo – but most fighters wore a helmet and light armor, and fought with some variant of a sword and a shield. So, when reconstructing gladiator physicality it is important to focus on this “average” situation.

Then there is the question of diet, brought to the forefront by the documentary Game Changers, which posited that gladiators were entirely vegetarian. This claim does have merit, with tangential support in primary sources and in osteological study of gladiator remains. However, in order to push its point that veganism is the “best diet”, it makes too hasty a conclusion and paints an incomplete picture. This claim hinges on two (true) points:

Gladiators were sometimes called hordearii, meaning “barley-eaters”.

This point is true; the gladiator diet was primarily based on cheap grains. While they were athletes and investments, they were still slaves, and were fed as such. However, this was not a purely logistical decision. If it was simply a matter of housing and feeding them as cheaply as possible, luduses would not have had baths (a luxury), and the diet would have ended at barley-based gruel. Also, as discussed earlier, the level of cardiovascular exertion in a fighter’s training is almost incomprehensibly high; they would need an immense amount of carbohydrates to keep up. So, eating a grain-heavy diet makes sense. Also, the aforementioned layer of subcutaneous fat was important for self-protection.

There’s also the issue of the drink gladiators were known to consume during training – a concoction of water and plant/bone ash. If the whole ethos of the gladiator diet was to stay cheap, why bother with this “sports drink”? This element indicates that, rather than being mere cannon fodder, gladiators were athletes that their owners invested in heavily, to the point of developing specific products for better performance. Everything in gladiator training was intentional and designed to maximize performance, to the best extent possible with information available at the time.

A 2014 study analyzed the strontium-calcium ratios of gladiator remains, and this measure indicated that gladiators likely did not consume much meat.

This is a simple question of (perhaps intentionally) misunderstood data. The ratio of Strontium to Calcium in a mammal’s skeleton indicates, generally, their diet; bones heavy in strontium indicate a more herbivorous diet, while bones heavy in calcium indicate a more carnivorous diet. The 22 gladiator skeletons in this study were found to be mostly in the range of omnivorous to herbivorous, trending toward the latter, and with this point made, Game Changers closed the book on the gladiator diet and declared them vegetarian – allegedly, they were just extremely early adopters of WEF dietary recommendations.

This was almost certainly not the case. First of all, depictions of gladiators tend to emphasize their muscularity, which could not have been developed without sufficient protein. Second of all, the study in question examined gladiators from a site in Ephesus, Turkey – on the coast of the Aegean Sea. The cheapest seafood during the gladiator era – mollusks – are extremely high in strontium, to the extent that people who regularly consume oysters, clams, or mussels can appear to be vegetarian by their strontium-calcium ratio. So, these fighters probably got most of their protein from this local source. Interestingly, similar data for gladiators from other regions of the Roman Empire has not been produced, and it seems that this study was selected intentionally to paint an incomplete picture.

Between this dietary information, primary sources on training, and inferences about physical requirements, one can fairly accurately depict gladiator physicality. They were above-average in size with some (but not much) subcutaneous fat, extremely cardiovascularly fit, fast, and had powerful arms and legs.

Rather than mere slaves put into the meat grinder for entertainment, they were great athletes, fighting for many of the same reasons as modern boxers. Their social position was intricate and contradictory (and uniquely Roman) – but their purpose was victory, and they lived, trained, and ate with that goal in mind.

Of course, this is just a thought experiment, but certain similarities can be drawn to modern athletes. In my view, the nearest modern parallel would be light heavyweight (or heavyweight) fighters in MMA or boxing. They have all the same physical elements, and their sport is quite similar in requirements.

Also, parallels can be drawn to the requirements of certain football positions – for example, linebackers or defensive tackles. Their combination of speed, aggressiveness, and physical power is comparable in many ways to gladiator fighting.

Generally, someone like Brock Lesnar, Don Frye, or Aaron Donald probably wouldn’t have looked too out-of-place in the Colosseum.

Excellent article. All reasonable points and well thought out.

So many professional historians tend to find a bit of data and come to the conclusion that, "because of this scrap of evidence, 'X' must have been the norm." Meanwhile excluding common sense and reason.

The Romans were above all pragmatic, and recognized what worked and what didn't. They weren't some alien species that ignored human realities and did things willy-nilly.

So it seems likely, that just as modern MMA fighters are treated, the untested fighters at the bottom would have existed on the edge of poverty, i.e. barley and sardines being the modern equivalent of canned tuna and ramen noodles.

But it also seems reasonable the championship contenders would be given the finest meats, women, trainers, doctors, etc. by their owners.

Common sense tells us that you can't build a winner by starving and mistreating them. Heck, that even applies to horses and show dogs, let alone champion fighters.

Subcutaneous fat would provide NO additional protection from edged weapons. A gladius certainly doesn't care whether you have extra fat or not. The gladius Hispaniensis and Mainz gladius were cut and thrust swords capable of delivering devastating shearing blows. It's not going to be bothered by fat. Later types were designed primarily for thrusting, which again, won't care if you have extra fat.

ANY cut by an edged weapon that breaks the skin has the potential of being dangerous. Fat isn't going to make a bit of difference.

We also have the writings of period physicians which directly contradict the idea of gladiators having extra fat (Galen wrote disparagingly of the notion, and surviving training manuals explicitly call for lean bodies without excess fat).