Refinement Culture in Martial Arts [Part 1]

"The fixation with quantifiable success can lead to a collective flattening of the human experience"

In 2021, Paul Skallas (aka LindyMan) coined the term “refinement culture”: the trending of everything toward sameness and optimization, from fashion to architecture to sports and everything in between. His work is primarily focused on the modern forms of this effect, such as the optimization of professional sports via statistics, or the unending sameness of ultra-modern apartment buildings.

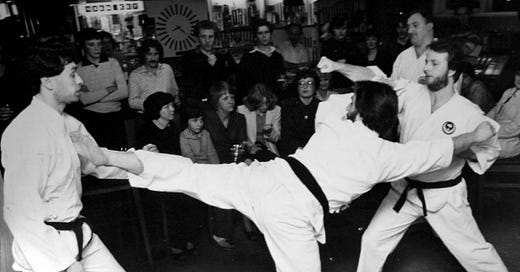

But refinement culture isn’t a new phenomenon – in fact, it’s quite Lindy itself. The development of martial arts into their modern forms is an extreme example of refinement culture, executed over the course of centuries and pruning far more than most realize.

A Note on the Paywall:

This article is the first in a series of more in-depth martial arts essays, which will be posted every week for the next 20 weeks. They’ll be limited to paid subscribers, but I will continue to post free content here as well.

Pre-20th Century

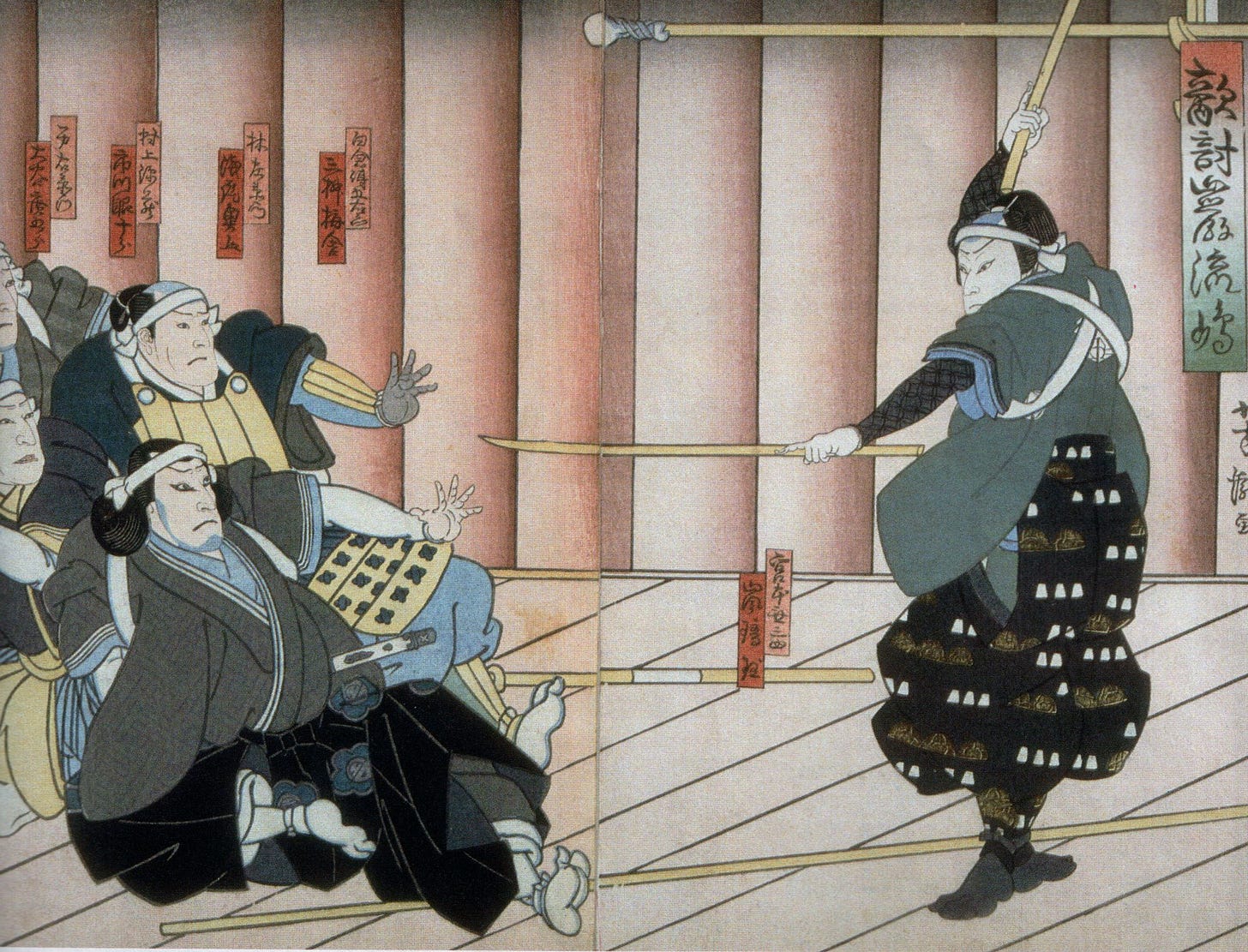

Solely in the realm of Japanese martial arts, this effect of refinement culture on martial arts is extremely clear. Consider kendo, the most popular form of Japanese fencing: practitioners wear uniform protective gear, fighting with a bamboo sword meant to replicate the feel of a katana. Target areas are limited to the hands, face, chestplate, and neck. There’s variation in style between instructors, but it’s largely quite similar – practitioners focus on explosive speed and greater reach, with similar flat-footed stances and two-to-three-technique combinations. This form of competition arose in the eighteenth century, and the rules largely haven’t changed since the nineteenth century, nor has the equipment or techniques. Many schools still draw their techniques from Chiba Shusaku’s Sixty-Eight Techniques of Kenjutsu, published in the early days of the sport, and later refined into a single series of forms in 1912 (the Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kendo Kata).

But Kendo arose from a far more diverse tradition. It began, like many other forms of martial arts competition, out of a need for safe training; samurai obviously couldn’t spar with sharp swords, and even wooden bokkens can cause great injury, similar to that of a baseball bat. So, the flexible bamboo shinai was adopted, and competitions with it became a popular way for swordsmanship schools to prove their worth against competitors. But these swordsmanship schools had an incredible amount of regional diversity, in everything from their training methods to philosophy to weapon of choice, all of which was streamlined for the narrow kendo ruleset, in the interest of fair competition.

However, this ruleset massively narrowed down the scope of weapons-based fighting in Japan. Aside from the earliest adopters (three major schools around Tokyo), most of Japan’s once-diverse sword schools predated the earliest kendo competition by 200 years, having been established during the relative anarchy of the Sengoku Period, also known as the “Warring States period” (1467-1638). The samurai Miyamoto Musashi was born in 1584, and wrote extensively on the state of swordsmanship in his time, having unknowingly been born into the most diverse era of Japanese martial arts. In his work The Book of Five Rings, Musashi details dozens of other schools – of course, aiming to demonstrate their weaknesses.

These competing schools included systems that used extremely long swords (tachi or nodachi); shorter swords (wakizashi), sometimes in pairs; oddity weapons like the chain-and-sickle; spears, halberds, etc. There were schools that trained heavily in speed, and schools that emphasized strength; schools with incredibly complex techniques, and others with just a few. He describes different types of footwork (“floating foot, jumping foot, springing foot, treading foot, crow’s foot…”), different ideas on where to affix the eyes, defensive vs. offensive schools, and widely varied philosophical traditions. The entire Book of Wind – 1/5 of the work! – focuses exclusively on these competing ideas about strategy and fighting. Contrast this with modern kendo, and you can easily see the refinement of all these traditions into a single, “optimized” art.

However, while Japan’s case is compelling, nowhere else has refined their martial arts as much as Europe. After millennia of martial tradition, the sports that remain are boxing, wrestling, and fencing, all governed internationally under the same rules and quite foreign from their wilder ancestors.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Letters from Hyperborea to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.