On the Sword

"A properly balanced sword is the most versatile weapon for close quarters ever devised… Its worst shortcoming is that it takes great skill, and patient, loving practice to gain that skill" -Heinlein

Beneath the raised sword lies Hell, which you dread; but if you move ahead, you will find the Land of Bliss.

-Miyamoto Musashi, The Book of Five Rings

I firmly believe that everyone who seriously trains in martial arts should study the sword.

Many do not agree with this opinion, especially the “tactical self-defense” types. Their objections are valid; this is the twenty-first century, and nobody carries a falchion or wakizashi for protection anymore. But the sword is important not because of its actual use in “combat”, nor for its direct carryover to other aspects of “realistic” fighting. In fact, it has very little transfer value to any other fighting system. The footwork of any type of swordplay is near-identical to the footwork of other martial arts from the same region, so it won’t give much new insight there except through repetition. Besides, its techniques are largely not applicable to hand-to-hand fighting. They are entirely unto their own.

So why even bother?

In this post, I’ll delve into a few primary reasons, and give some examples.

First of all, and most importantly, swordplay is incredibly technical. I’d even venture to say that it is the most technical of all types of fighting, especially when using a two-handed sword like a katana or longsword. All of the same principles of timing, distance, speed, and body mechanics still apply, but they are greatly complicated by the armament involved, and the physics of both using it yourself and manipulating the blade of your opponent.

The lever principle is applied in ways previously unseen to most fighters, and training with a sword makes its application second nature, which will greatly improve mental acuity and flexibility when fighting. Because of the additional reach a sword provides, bad footwork is punished far quicker and more harshly than in hand-to-hand sparring, which forces more careful thought about it in general. Swordfighting is a thinking man’s game, and as a result, it will broaden the mental game of anyone who crosstrains with it on a serious level. When you constantly force complex decisions on yourself under duress, eventually making these decisions will become easy. Then, after enough time, they’ll become instantaneous – in the best-case-scenario, they will become completely subconscious. Many martial arts theorists and writers talk about getting used to entering a “flow state” when fighting, which of course important, but many fail to address how to expand your abilities in this state, only focusing on how to more effectively enter it. In my experience, sword work expands your technical and mental prowess, allowing you to see more openings and possibilities, and generally makes you a more competent martial artist. It is weightlifting for the part of your brain that deals with fighting.

Another critically important reason to train with a sword is more difficult to quantify or explain. In outlining the technical aspects, I touched on how sword work reveals weaknesses and punishes them. This is true, but the concept goes much further than revealing mere missteps in footwork or bad timing; swordfighting reveals mental and spiritual deficiencies far more easily than typical sparring. Issues in mindset or commitment, which might take years of serious training to reveal, tend to surface quite early in sword training. For example, many people pride themselves in their “aggressiveness” while fighting. However, too often this aggressiveness is false confidence, stemming from too-easy opponents, too-light contact, or too-nice training partners who won’t fully exploit easy openings in the name of providing a learning experience. Aggressiveness in the gym doesn’t always extend to real fights, either in the ring or on the street. Training with a sword is one indirect way to reveal this deficiency, and to work on it. The constant threat of a blade aimed directly at your face is an awfully good deterrent against launching hapless attacks, and many “aggressive” fighters crumple under this pressure, reverting back to slow, careful, defensive fighting. It is incredibly difficult to fight aggressively with a sword, and learning to do so tempers one’s resolve, which extends extremely well over to hand-to-hand fighting.

On Aggressiveness:

“Holding Down the Pillow” means not allowing the enemy's head to rise. In contests of strategy it is bad to be led about by the enemy. You must always be able to lead the enemy about. Obviously the enemy will also be thinking of doing this, but he cannot forestall you if you do not allow him to come out. In strategy, you must stop the enemy as he attempts to cut; you must push down his thrust, and throw off his hold when he tries to grapple. This is the meaning of "holding down the pillow".

When you have grasped this principle, whatever the enemy tries to bring about in the fight you will see in advance and suppress it. The spirit is this: check his attack at “a”; when he jumps, check his jump at “j”; and when he cuts, check his cut at “c”. The important thing in strategy is to suppress the enemy's useful actions but allow his useless actions. However, doing this alone is defensive. First, you must act according to the Way, suppressing the enemy's techniques, foiling his plans and thus commanding him directly. When you can do this you will be a master of strategy. You must investigate this thoroughly.

-Musashi

Related, but not one in the same, is the issue of “committing” to techniques; following through with full power and – more importantly – full intent of completing the strike. It is easy to develop physical prowess and basic technical knowledge in unarmed fighting, and then never use it to its full extent. Pulling punches in training is addictively easy; I’m not referring to striking power here, but rather how easy it is to not commit to your strikes during sparring. Many, if not most, martial artists go through this phase of wishy-washy fighting because it is rewarded rather than punished in point-based or light-contact sparring. If you never commit, you can always change your course of action, so why not, right? The problem only comes when those fighters try full-contact fighting or are thrust into a self defense situation. Especially in the latter case, their opponent will commit 100% to their strikes, and as a result, beat the trained fighter to a pulp because he does not do the same.

Sword work, however, forces commitment because of its technical nature. You cannot halfway parry something, because you will get cut; you cannot half-commit to a thrust, because it will not hurt your opponent. When closing the distance, you cannot be wishy-washy, or you’ll get slashed. When fighting, but particularly when swordfighting, you must believe in your choices fully and execute them without hesitation. Flow like water, yes; but if you still strike like a wet rag, you won’t cut anything, and will quickly die to even a weaker opponent. Even fighting with symbolic life-or-death stakes shocks most practitioners into committing more fully to their techniques, and is one significant reason that I recommend this type of crosstraining.

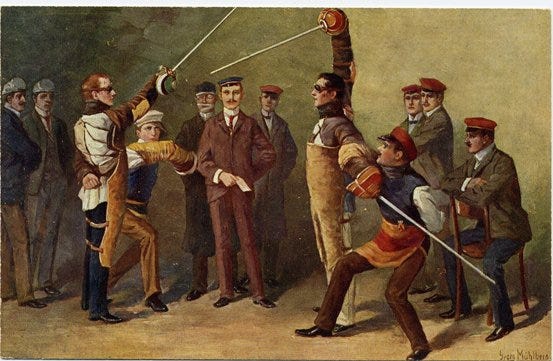

To further this point, let us examine a historical example of the spiritual and mental aspects of swordfighting: mensur, the German art of academic dueling.

Popular from the eighteenth to the mid-twentieth century (and still occasionally practiced today) mensur is not a martial art or a fighting system; rather, it is a test of courage and mettle, as well as physical prowess. Practitioners (university students) stand at a regulated distance apart – well within the range of their swords – and do not move throughout the contest. The blades used are sharpened, and very little protective gear is worn. The objective is not to “win”, but rather to demonstrate one’s ability to face the trial of combat with resolve and courage. Flinching or dodging is not permitted. Scars earned during mensur, especially on the face, were (and sometimes still are) worn as badges of pride. The whole affair is meant to educate and strengthen character, rather than to settle any dispute or decide a winner.

You don’t necessarily have to spar with live blades or have your face slashed, but sword training in general is hugely capable of strengthening these aspects of a martial artist. However (and I will expand on this later) sparring is deeply necessary to confer these benefits.

As an aside, there is a use case for sword training that I hesitate to engage with too directly: that is, self-defense and other real-world instances. In a self-defense situation, an improvised weapon can be handled like a sword, knife, escrima stick, etc., and training with these hand weapons helps to open that possibility if it is needed. There is also the case of increasing street rioting and fighting, especially in American and European cities, which some others have directed my attention toward as a potential application of training with hand weapons such as the sword. On this point, I’ll defer to Clark Savage’s excellent book King of All Things: “In these increasingly common disturbances, such street fighting may be considered combat in that there is often an intent to injure, yet firearms are considered “too much,” and hand weapons, usually improvised ones, become the tool of choice.” If faced with that situation, knowing how to handle something vaguely sword-shaped could be helpful.

But I digress.

Before I advise on the specifics of sword work, allow me to present one final reason often overlooked by martial arts writers. It’s fun. Training swordplay presents unique opportunities for technical and spiritual growth, but it’s also a nice break. Keeping training refreshing and interesting is what keeps people training for years, and crosstraining helps immensely. Repetition is and always will be king for steady improvement, but without breaks it makes training dull and uninteresting – a chore rather than a passion. If you’re like me, you’ll appreciate the variety of training and dive into history that swordsmanship provides. Swords have traditionally been carried as a self-defense weapon and sidearm on the battlefield, and the techniques that arose from their specific uses always have deep and interesting historical contexts. I’ll expand more on this later, but it is a fascinating aspect of studying an antiquated system of fighting. Even if this doesn’t interest you, though, the other points still certainly apply.

But now that we have established the “why”, how does one make sword training effective and interesting?

Allow me to refer back to my tenets of martial arts training. This section will get rather specific, so if you’re just getting into martial arts and reading this for inspiration, it might not be helpful – yet.

REPITITION IS KING

This is always true. When learning basic techniques and combinations, practice them to perfection and then continue to practice them. It’s such a simple aspect of martial arts, yet many do not fully appreciate exactly how much one must train to attain even a moderate level of skill. Kata-style training with a sword is critical mostly in the early stages of learning, but should be practiced indefinitely. Precision is key; make sure your strikes start and land at exactly the same spot every time. Practice slowly to perfect blade alignment and proper form, then speed it up and chain techniques together. I’ve said this before but I’ll reiterate – body mechanics are much more detailed and important with sword work than with typical hand-to-hand fighting. The exact orientation of your wrists and ankles, as well as your exact grip on the handle, can seriously affect your ability to strike properly. Focusing on this level of detail is one of the most important reasons to crosstrain with a sword, and it cannot be ignored during training. Exactly what you practice with will vary between systems and schools, but generally, a wooden sword is preferred. Metal training swords are expensive and often poorly made for their purpose. If you’re training on your own or with a partner, definitely get a well-made bokken or other wooden replica, as they can take a lot of abuse and they’re dirt cheap to replace when they finally do break. Personally, I’ve beaten wooden bokkens to the ground, splintered them badly, and repaired them with electrical tape for another few years of use. Allegedly, Cold Steel’s polycarbonate replicas are also good for this purpose, but I don’t have enough experience with them to personally recommend them.

The second important part of repetitive training with a sword is partner drills. These are critical for developing spatial awareness and footwork against an opponent. Chaining two or three techniques together and practicing them consistently, from different positions and different distances, is a simple but proven way to commit them to memory. Plus, once you understand the basics, creating new combinations and drills is a fun and helpful way to explore the near-infinite possibilities of swordplay. Personally, I learned a lot about body mechanics and timing from choreographing staged swordfights, and improved my general weapon handling in the process.

As an aside, many people study swordsmanship on their own, which is a difficult subject to address. Personally, I’ve had a mixed approach – I learned the fundamentals with instructors, then deepened my knowledge with individual/small group study and practice. In general, I would not recommend learning from the ground-up completely alone. If you already have significant martial arts experience, further study can be done effectively outside of the gym, but at least the basics require the expertise and eye of an experienced instructor.

Training morning to night, once you have polished it to perfection, you will achieve an independent freedom, naturally also acquire wondrous abilities, and have mysterious, limitless power. This is the spirit of the practice we undertake as warriors.

-Musashi

FIGHT HARD AND OFTEN

Most sword training avoids sparring due to its inherent danger, even with blunt weapons. This is fair, but you won’t learn anything except a few techniques without putting your knowledge to the test. As with any other martial endeavor, you must constantly spar at different levels (and ideally, with different opponents) to learn anything actionable.

I won’t go into depth about methodology here, but remember that swordfighting is inherently extremely dangerous, even with blunted or wooden/synthetic weapons. Danger is a potent and important thing to confront in life – and a necessary one, if you’re training to fight. No matter what precautions you take, just know that you will get hurt. Legal counsel has advised me to say that you should always wear proper protective gear and use padded or otherwise neutered weapons. In general, though, I’ll say this: keep it safe, but not so safe that you’re totally unafraid of being hit. Confronting and defeating the fear of losing catastrophically is an important part of learning to fight.

In the strategy of single combat also, it is vital to menace with your body, menace with your swords and menace with your voice – things that your adversary does not expect, suddenly do, and perceiving the moment of his fear, immediately gain victory. You should test this out thoroughly.

-Musashi

GROUND YOURSELF MORALLY AND PHILOSOPHICALLY / RETURN TO TRADITION

Any proper training should ideally cover this aspect. Respect the weapon that you’re using, its purpose, and why you’re doing it. Remember that you’re training to become a better martial artist; don’t treat it as “playing with swords”. When training with antiquated weapons, you’re tapping into a rich historical tradition of men who made their livings in blood and staked their lives on the effectiveness of their fighting systems. Every technique and piece of knowledge was gained at the price of deep scars, lost limbs, and brutal deaths. When you pick up a wooden sword to learn cuts, parries, and thrusts, you’re reigniting a long tradition of men who did just the same, knowing their lives would soon depend on those skills.

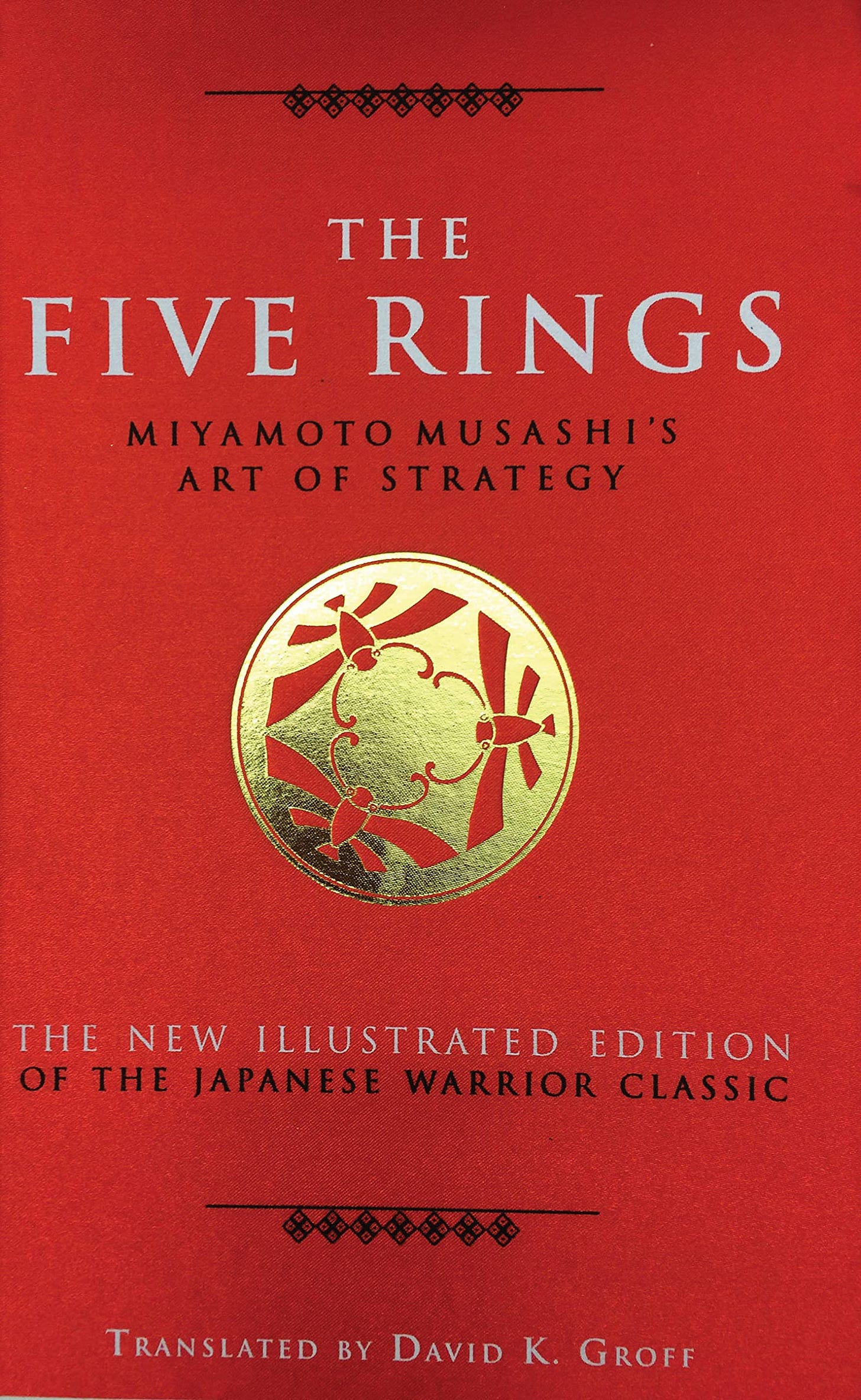

This is also where the historical study aspect comes in. I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again: read The Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi (this is the best translation). It deals extensively with swordsmanship and sword combat, and the source is certainly reliable – Musashi was undefeated in dozens of duels to the death, and later in life would take challengers while wielding only a bokken (wooden sword), or even an oar, against his challengers’ sharp weapons. Besides, it’s by and far the best work ever written on the subject. For further study, especially if you are interested in European swordsmanship, the translated works of Fiore de Liberi and Johannes Liechtenauer are widely available online, and very helpful if you’re willing to work through writing that is occasionally confusing/difficult.

This aspect also gets into the contentious realm of what system one should study. The only sword arts with a living, continuous tradition come out of Japan, China, and Korea. Of these, only the Japanese arts are based on actual combat usage. These are Kenjitsu, Kendo, and Iaido. Kendo is much like Taekwondo, in that it is a sportified version of a historical fighting system, and it should be treated as such. It teaches the fundamentals effectively, but is limited in scope by its ruleset. Its practitioners develop extremely good distance and timing, incredible reaction time, and blazing speed – however, creativity is not well-developed and striking areas are limited. Kenjitsu is more of an overall fighting system, but sadly most modern schools have almost no focus on sparring. The focus on kata means that its practitioners develop stellar technique and balance, but without sparring they lack the timing and “fighting mindset” of kendo. The same goes for Iaido, which is primarily concerned with fighting “from the draw”, Wild-West style. Schools for any of these arts are few and far between, so your best option will probably be to learn from an instructor of another martial art who has experience in swordsmanship, and to pursue further study on your own.

Then there is the issue of HEMA – Historical European Martial Arts. This is a relatively recent invention, based on the reconstruction of European fighting systems from translated manuals, such as those of Fiore or Liechtenauer. HEMA classes are primarily focused on practical sparring, which I respect, but outside of that the art is of variable quality. Its practitioners are typically out of shape, chronically online, and have little experience with other martial arts. I believe this stems from HEMA’s online-based community and its core conceptual issue: that reconstructing a martial art from a few writings is incredibly difficult, and relies heavily on guesswork. Also, competitions are few and far between, typically with restrictive and confusing rulesets that limit creativity and the use of physical strength – exactly what you don’t want in a developing martial art. It’s interesting as a concept, and may become a more broadly workable endeavor in a few years, but as of now it’s so different between schools that I’m tempted to classify it as belonging to the realm of internet warriors and hobbyists.

This thing called “strategy” is the practice of the warrior class. Those who command must carry out this practice, and those who fight should also understand this path. […] Few, however, care to follow the path of the warrior. A warrior has what are called the Dual Paths of Scholarship and Warfare to follow, and must have a liking for both of these Ways.

-Musashi

CONSTANTLY EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

Because of how limited modern swordsmanship training actually is, any study of the art is typically self-directed and aimed at expanding knowledge. The act of sword training alone is an element of expanding one’s knowledge, and if you have the time for it, it is a worthy endeavor for any martial artist looking to broaden their horizons.

As for the Way of strategy and single combat, in all things you must be constantly intent on taking the initiative, always taking the initiative. The idea of “taking up a position” means waiting for someone else to take the initiative. You should work this out thoroughly.

-Musashi

On HEMA

"Its practitioners are typically out of shape, chronically online, and have little experience with other martial arts"

True, unfortunately. Probably worth noting that this is not true of many of the top rated guys (eg. Kristian Guivarra and Sergei Kultaev, 4 and 5 here, are both (former?) boxers: https://hemaratings.com/periods/details/?ratingsetid=1 )

"HEMAs... core conceptual issue: that reconstructing a martial art from a few writings is incredibly difficult, and relies heavily on guesswork"

There's more than 'a few' writings and those from the Renaissance onwards don't require much guesswork, frankly. Joachim Meyer's 1570 text (on German fencing -- two-handed sword, sabre, early rapier, some other non-sword stuff), for example, includes pictures illustrating body mechanics quite explicitly, descriptions of techniques, and plenty of advice on strategy. Salvator Fabris (writing in 1606 on rapier) has all that and a far more accessible style to modern readers (Meyer is about as clear as that Musashi quote about stopping their cuts at c, ie. it makes sense once you've practiced swordsmanship enough). You're correct in that Medieval texts are pretty much just catalogues of techniques, often poorly described, and require a fair bit of interpretation but this is not universally true.

"competitions are few and far between"

Drivel.

Past: https://hemaratings.com/events/

Future: https://sigiforge.com/events/

"typically with restrictive and confusing rulesets that limit creativity and the use of physical strength"

???

I am a new HEMA guy and have only attended three comps so far (all in the past six months, since I started in 2020; few and far between indeed) but there have been no target or technique restrictions beyond don't strike the back of their head (which is poorly protected by typical fencing masks), don't punch, don't kick, don't grab the head or body (you were allowed to push or pull their hands in all three of them). This seems fair since it's supposed to be a swordfighting competition. The most arcane rules have been based on how long you're allowed to keep fighting once a blow has been struck but I'm not sure how that relates to creativity or physical strength (taking a sword to the face in order to get a hit is bad strategy). In the interest of not being disingenuous, one comp I attended had narrow rectangular 'rings' that made nonlinear movement impossible but that's not typical -- and there was a lot of complaining about it. Perhaps you would like to provide some examples?