I try not to write in too much detail on fighting.

It’s inherently something you must experience rather than read about, something to be learned in the physical dimension rather than on a page. I can’t explain the feeling of taking a punch to the face to someone who never has any more than I can describe the color blue to a blind man. The experience of fighting is near-impossible to transmit via the written word. Many writers have tried, but very few have published a worthwhile treatise. Among the best works are The Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi; certain writings by Bruce Lee; the manuals of William Fairbairn, Eric Sykes, and Rex Applegate; Meditations on Violence by Rory Miller; and recently, King of All Things by Clark Savage. But again, you can read these works cover to cover and not understand what they mean unless you go out and apply them.

With this short piece, I don’t aim to approach any of those works in scale or philosophy, or transmit something that only real-world experience can. However, I do believe I can offer some insight on how to train and how to think about training, based on personal experience as both trainee and instructor.

With that said, these are in my view the five tenets of martial arts training. I wrote them as exhortation after a few hours in the gym, so the tone is a bit aggressive, but I hope they transmit the point.

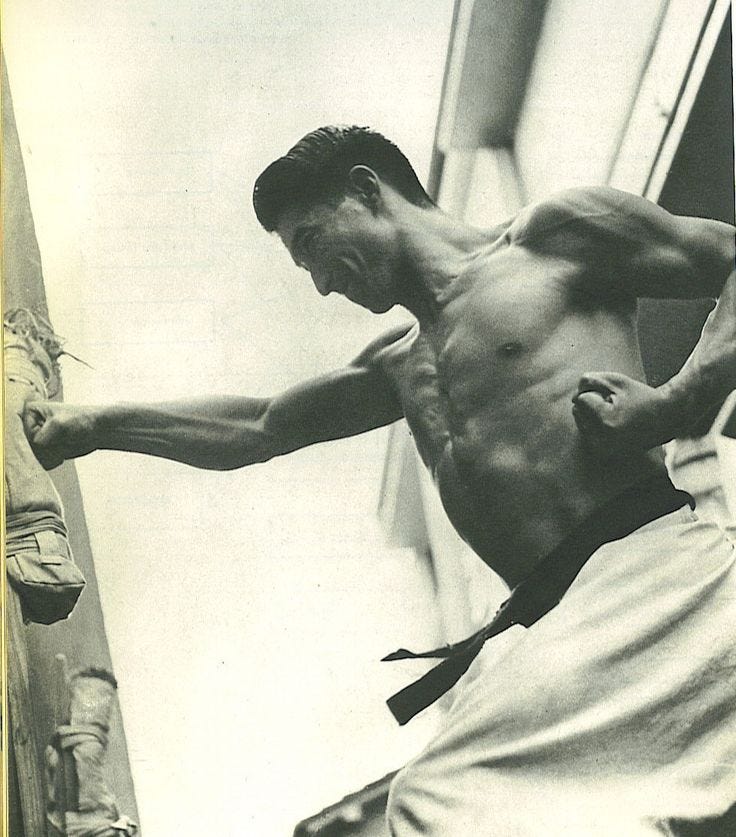

REPITITION IS KING. Any form of training is useless without constant, repetitive upkeep. You must drill techniques until they no longer feel like techniques, but are completed with the same ease as every step in a casual walk. When you have reached a point of proficiency with the basic techniques, the same must be undertaken with combinations; however, continue repeating the individual techniques, in as many situations as possible. The ability to strike, to move, and to defend must not be a skill set you possess, but rather a set of reflexes and actions ingrained into your blood, undertaken with the same level of assuredness as a wild ram butting heads with a territorial rival; not just a knowledge base, but a set of actions etched into your soul. There is no replacement for this. Every day, every technique, every variation, every situation. Without this, you cannot call yourself a martial artist; you are simply someone who has practiced some fighting. Traditionally, warriors and fighters (there is a distinction) trained upwards of eight hours a day. A one-hour BJJ class will never get you to their level if you don’t supplement it with individual practice, whenever you can. Practice side kicks in the handicapped stall at work if you have to. Repetition is absolutely critical.

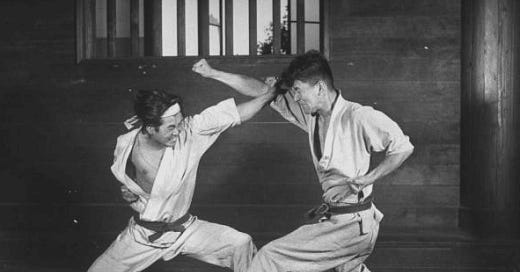

FIGHT HARD AND OFTEN. Repetition is what teaches you martial arts, but fighting is what makes you a martial artist. You cannot become a fighter without fighting, in the same way that you cannot become a painter or an astronaut without painting or going to space. Any school that “doesn’t spar” is run by frauds, and they should be ousted from their place in the local community by actual martial artists (it wouldn’t be very hard, considering their incompetence in combat). Any school that doesn’t spar “hard” is just as bad, if not worse. They instill false confidence, which is a liability to their students. Of course, you can’t spar hard every day, but a total lack of heavy competition is extremely detrimental. If you are not comfortable punching someone with full intent to injure, or being punched with that same intent, you will falter when it matters. And the only way to become comfortable with these things is through repetition – once again, repetition is king. You must fight often, and you must fight hard. You must feel at home covered in bruises and blood. You must fight as though you were born to do so, because you were.

GROUND YOURSELF MENTALLY AND PHILOSOPHICALLY. Ignore the philosophies of most modern martial arts systems. “To end all conflict by making it unnecessary” is idiotic, as are most Buddhist-sounding neologisms. Your goal is to become more proficient in the use of violence. Your goal is to struggle so hard that you come out on the other side a wilder, more refined individual. With that said, you must study the greats and learn from them. Musashi in particular is required reading. Fighting, like baseball, is 90% mental; the other half is physical. You must understand the nature of conflict and the nature of yourself. This takes intensive study and reflection. Meditate, even as you train. The best fighters train with a blank mind, often in silence; you don’t need a TikTok-style dopamine flood the entire time. In fact, this is detrimental. Training outdoors is excellent for this; as New-Age as it sounds, you need to be able to empty your mind on command.

RETURN TO TRADITION. Martial traditions are born out of centuries of bloody warfare. They didn’t arise for no reason at all; they arose because someone, at some point in time, needed to bash someone else’s skull in with consistent effectiveness. Everything developed in the history of an art that was not developed during a time of active conflict should be disregarded; i.e. anything recent. Every martial art started out having “teeth” and being lethal; otherwise, they wouldn’t have ever gotten off the ground because their practitioners would be dead. People dedicated precious hours of their days and years of their lives to the development of these arts, in the pursuit of mastery over violence. Today, that is not the case, so your best bet is to return to the source and thoroughly consider the need, context, and philosophy behind the original version of every technique and training method. Train like a warrior, not an athlete or a showman. Train traditionally, without the crutches of modern technology or accommodation. Fighters still cut down trees with roundhouse kicks in Thailand — going “easy” on yourself is a particularly modern form of weakness.

CONSTANTLY EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE. So you know Muay Thai and Brazilian jiujitsu. Maybe you’re on par with UFC fighters in terms of skill in these arts. Those are the best fighters in the world, so you should be set, right? Just train them some more? No. Learn Judo. Learn karate; compete in kyokushin. Take up boxing. Wrestle, Greco-Roman style. Study hapkido. Hell, try Wing Chun. There is no shortage of things to learn and ways to improve. The day you become stagnant is the day you die. You are a shark; you must keep moving forward, and expanding your domain of mastery. A martial artist that stops learning is no longer a martial artist. With that said, the end goal of fight training should not be to have many techniques; it should be to have no technique, only instinct.

There is much more to be said about fighting, but in my view these are the key elements of proper training. In the coming days I’ll expand on certain particularities and practices, but these tenets are always at the core of my thought.

As a final point, I’ll leave you with this: AGGRESSION IS A SKILL. I don’t consider it a core tenet of training, but it’s important and often disregarded by modern “defensive” schools of fighting. Just remember — you are training to become better at aggression, better at the use of force, better at dominating an opponent physically. This is the goal; or, as some would say, “this is the Way”.

Excellent advice