The Allied submarine effort in the Pacific during the Second World War has retrospectively been considered a great success. Submarines delivered heavy losses to Japanese merchant shipping and managed to sink multiple vital warships, hampering Japan’s economic strength and the IJN’s tactical advantage to a significant extent. However, these successes were not achieved immediately, and during the early months of US naval involvement in the Pacific, the submarine effort was disastrously ineffective. The submarine force was plagued with structural issues, from the ground up (or, rather, the seafloor up). Poor engineering, inadequate command selections, misguided training, underdeveloped tactics, and errors in grand strategy all contributed to a submarine force which was thoroughly incapable of achieving its goals in the first months of the war. The US Navy’s ability to adapt and overhaul is a testament to its flexibility during the war, but the period during which these issues were identified and corrected led to many lost ships and sailors, as well as missed strategic opportunities. Understanding this initial crisis is critical to understanding the overall naval situation in the Pacific, and makes the Navy’s eventual success in the region all the more impressive.

At the outset of the war, the most general problem facing US submarine action against Japan was one of organization and grand strategy. Before the war, the submarine force had been divided into the Atlantic, Pacific, and Asiatic Fleets. The designations for these fleets shifted throughout the war, but most critically, they remained somewhat separate entities, under separate commands with no real unity in strategy or communication. ComSubWesPac operated southwest of (approximately) the Luzon Strait, and ComSubPac operated everywhere to the northeast of this dividing line. As a result, the Luzon Strait – an important convergence point for Japanese merchant shipping and warship movement – was initially left untouched by US submarines due to worries about overlap and potential friendly fire between submarines from the separate commands on unrelated missions. The US Navy, by means of inefficient organization, left one of the most important shipping lanes untouched for over a year of critically important warfare. Additionally, due to the high degree of independence associated with submarine missions, there was very little operational unity to the effect of achieving grand strategic goals. A high degree of secrecy was upheld even within and between the commands in order to avoid submarine operations becoming public knowledge, as the campaign of unrestricted warfare was technically in violation of the London Naval Treaty.

Another initial command failure of US submarine action in the Pacific came in the specific tactics implemented for patrols. Submarines were sent out alone, with a designated patrol area and a specified return date. They were expected to maintain radio silence during their patrols and attack as many targets as possible before returning, barring any technical failures. However, one submarine is inherently limited in its tactical ability; fundamentally, once a submarine engages an enemy convoy, it “shows its hand” and must immediately evade or gamble on attacking again, assuming their initial salvo did not sink the entire convoy (which happened more often than not). At this point, the German navy was already using wolfpack tactics to great effect in the European Theater, but such tactics were not adopted by American commands until later in the war. During the strategic era of single-submarine patrols, many submarine captains were frustrated with ineffective fire control and the dangerous chases that ensued after an ineffective torpedo salvo. Many submarines were presumably lost in this manner, as Japanese sonar technology was typically incapable of detecting a skillfully commanded and crewed submarine until it actually attacked. On the other hand, a wolfpack could take advantage of the immediate response to a torpedo attack, veering off in different directions or allowing one submarine to draw the wounded convoy into a trap – an easy torpedo shot from another sub. In his landmark work Silent Victory, Clay Blair argues that wolfpack tactics were naturally more effective given the technology of the time, and should have been immediately adopted:

“[Wolfpack tactics] increased area coverage, brought greater firepower to bear on a given Japanese convoy or Heet unit, and befuddled antisubmarine vessels. It also worked to increase the aggressiveness of submarine skippers. A skipper operating alone could be as cautious as he pleased, avoiding the enemy altogether if he were of that mind. A member of a wolfpack would find it difficult to avoid a fight when his packmates were attacking and exposing themselves to danger. However, it would be a long time before the submarine force even considered wolf-packing.”

This other error that Blair refers to – lack of aggressiveness – is a difficult-to-quantify but certainly important factor. It had more to do with the Navy’s cultural conception about command promotions than actual tactical goals, but it factored into the implementation of submarine tactics nonetheless. The most effective submarine commanders in the Pacific – examples include Richard O’Kane, Dudley Morton, and Samuel Dealey – were not “typical” candidates for command. Their subordinates described them using terms like “fiery”, “intense”, and “calculating”; they were well-acquainted with risk and seen as unafraid of death. Because of the nature of submarines as fragile, stealthy, and slow-moving hunters, the general blueprint for a good submarine commander seemed to be an officer who was deeply careful and extremely detail-oriented, with a strong aversion to engagements with a potentially less-than-perfect outcome. The Navy also had a heavy emphasis on rigid adherence to seniority, which led to certain appointments which were perhaps unfit for the job, but had put in enough time that a promotion to command was deemed necessary. However, with the advent of unrestricted submarine warfare against a Japanese navy and merchant fleet with limited ASW capabilities, these risk-averse types tended to hamper themselves with excessive carefulness. They avoided engagements which in retrospect were perfectly tenable, to the detriment of achieving the submarine force’s strategic goals. However, their associates who took brazen risks (i.e. surfacing more, entering defended harbors, or attempting risky “down-the-throat” shots) returned to Pearl Harbor with drastically more tonnage destroyed. Blair’s argument about psychological pressure to engage certainly has merit, but more importantly, even risk-averse commanders would be more willing to engage if they had the wider array of options provided by a wolfpack. However, in the early months of the war, careful solo patrols were the status quo, which contributed to the general inability of the Submarine Force to sufficiently damage Japanese shipping and warship strength. This problem was only solved by a gradual upheaval in the ranks of submarine commanders, with many replaced due to unproductivity.

Beyond this late adoption of wolfpack tactics, numerous more specific tactical failures resulted from insufficient or misguided training. Prewar training emphasized technical proficiency and underwater operation of all necessary equipment, in keeping with the careful and stealthy approach to submarine warfare. This approach made sense in the context of a major fleet encounter on the high seas during daytime, or in a situation where a single submarine was faced with a squadron of warships. However, as seen in WWI, submarines were far more effective as commerce raiders, striking lightly-protected convoys under the cover of night or sinking warships moored in difficult-to-defend harbors. Those in the highest strata of US naval command failed to see this as a possibility, and instead focused on submarines as an instrument of major fleet action rather than separate vehicles for attritional warfare. So, training provided little emphasis on night-fighting, surfacing and reorienting during an encounter, or evasive maneuvers against faster destroyers – all situations that proved common during the actual war. Sailors and commanders achieved technical proficiency, but they were not acquainted with the tactical situation that they would face in the Pacific. Had the Navy broadened their vision of what submarines could and would do in a war against another major power, they could have prioritized more realistic and effective training – but they did not, and as a result, submarine actions yielded little fruit in the early months of the war.

This lack of proper training compounded another issue in prewar preparations: submarine crews were unused to the physical and psychological tolls of long, isolated patrols. Many submarine commanders did not even know how much food should be packed for a standard-length operation of one month in the Pacific. When crews and commanders are not sufficiently prepared for poor everyday conditions, they underperform in combat, no matter how technically proficient they may be; this is true of crews for any type of warship, but especially submarines, with their cramped conditions, lack of communication with the outside world, and at this stage, lack of air conditioning. The focus on majority-underwater tactics was compounded by a fear of Japanese aircraft, deemed “unnecessary” by Blair and Parillo, as Japanese ASW capabilities from the air were minimal and patrols were few and far between. Therefore, crews were unused to long-term missions and they were spending far more time underwater than necessary, contributing to even poorer living conditions (worse air quality, higher temperatures, etc.) – and as a result, worse performance than was achievable. These unforeseen poor conditions were compounded by the aforementioned tactical insufficiencies; crews endured these conditions only to return to Pearl Harbor empty-handed, deepening their frustration with the entire situation. To endure hellish living circumstances in the name of a successful patrol creates a hardened, focused crew; to endure them for nothing yields downtrodden men with low morale and consequently, low performance.

However, morale was far from the foremost issue at the level of each individual submarine. Between the generally outdated fleet and poor engineering in even the newest technology, American submarines were ill-equipped for combat against a peer in naval power. In December 1941, the fleet itself was composed of 55 fleet submarines of the Tambor class, built just prior to the war, and 18 S-Boats, which had been designed during the First World War and were significantly outdated. “S-Boats” refers specifically to the S class of submarines, built between 1917 and 1922, but other limited-run classes of submarine built during the interwar period were also referred to as S-Boats, or occasionally the “New S Class”. The Sargo class submarines were also sometimes included in this designation, though they were much more similar in purpose to the newer Tambor class, which was a true fleet submarine, meant for high-seas fleet action. Ultimately though, almost all of these submarines were outdated even as they first undertook patrols in the Pacific. They fired Mark 10 torpedoes, a WWI design; most lacked the range to operate in Japanese waters; and their top speed (as little as 14 knots for the S-Boats) was not practical for any mission besides scouting or coastal defense. Even the newest Tambor class had significant vulnerabilities; all its engines were situated in one compartment, making it extremely vulnerable to catastrophic chain-reaction failures in or out of combat. The Gato class, whose first boat had been commissioned on November 1st, 1941, mere weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor, would be the first US submarine to feature technology that could effectively combat the Japanese navy. But it would be months before US industrial might could begin to produce enough to create a formidable submarine fleet in the Pacific. So, the US Navy entered the war with an undersea fleet far below the capabilities of its surface fleet when taken in comparison to its opponents, specifically the IJN.

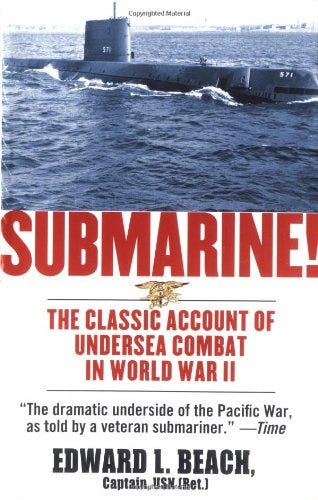

Even with this in mind, the single most glaring issue with US submarine technology during the early months of the war did not have to do with the submarines themselves, nor did it stem from a deficiency in tactics or command. Rather, the Mark 14 torpedo, seen as the most modern innovation in submarine warfare, simply did not work as intended. Despite the significance of every other issue with US submarine operations in the Pacific, this failure of engineering proved to be the greatest hindrance to effective submarine warfare. On the subject, Commander Edward L. Beach writes:

“Time after time, in the early days of the war, our submarine skippers reported that their torpedoes were not running where they were aimed; were not exploding when they got there; were going off impotently when they arrived; or were running in circles, with consequent danger to the firing ship. Written deep into many patrol reports, pathetic now in their vehemence, can be found the bitter words: “Torpedoes ran true, merged with target screws, didn’t explode.” “Fired three torpedoes, bubble track of two could plainly be seen through the periscope, tracked by sound and by sight right through target. They looked like sure hits from here. No explosions. Cannot understand it.” […] Torpedo after torpedo was fired under ideal circumstances. More often than not the only reward was the blank futility of ‘no explosions.’”

Beach’s deep anger at the malfunctioning torpedoes was shared throughout the submarine service, prompting dozens of letters of complaint to the Bureau of Ordinance. However, these complaints were largely rebuked, and the torpedoes’ failures were blamed on poor fire control, miscalculations, or other technical errors on the part of the captain or sailors. In reality, very few cases of torpedo failure could be blamed on human error. The Mark 14 torpedoes ran about ten feet deeper than they were set, and their triggers – both contact and magnetic – were systematically faulty. However, the Bureau of Ordinance was unwilling to reckon with this possibility, and continually deflected blame onto the submarine commanders or their crews.

Most attempted solutions to the ineffectiveness of the Mark 14 torpedoes only further complicated the problem, and the lack of proper diagnoses made for even greater issues with their use. Non-explosion caused some captains to blame the magnetic exploder and then disable it, instead aiming for contact hits. However, the real issue in many of these situations was the depth setting, and the magnetic exploder would occasionally be able to salvage a too-deep shot; but with it disabled, the result would once again be non-explosion. In reality, the contact exploder was less reliable than the magnetic exploder (which in fact was too sensitive, and would sometimes detonate prematurely). However, with no support from the Bureau of Ordinance, submarine commanders had to test their guesswork-based solutions on the battlefield, an inherently poor way to reach a conclusive solution. Once the torpedoes’ depth was suspected as an issue, some captains would order that torpedoes be fired with a zero depth setting, which could cause the torpedo to surface if it did not err in the same manner as other Mark 14s.

Eventually, complaints about the Mark 14 torpedoes became too prevalent to ignore, and prompted testing. The first tests occurred in Australia, ordered by Rear Admiral Charles A. Lockwood on June 20th, 1942 – seven months into the war. Lockwood concluded that the torpedoes ran an average of 11 feet deeper than set, more than enough to let them run under a target ship without effect. This test prompted the Bureau of Ordinance to finally reevaluate the Mark 14 with several rounds of testing. It was not until October of 1942 – after nearly a year of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Pacific, hampered by faulty torpedoes – that BuOrd would finally conclude that the torpedoes were poorly designed and improperly tested.

The case of the Mark 14 torpedo stands out as especially egregious, but it was merely one factor in the larger story of inadequate prewar preparation in the US. The Mark 14’s problems were unique, however, in that they were directly caused by the economic situation of the country; the Great Depression caused huge funding cuts across the cutting-edge elements of military research, including weapons design. Torpedoes were massively expensive to produce and minimal testing was done. The failures of the Mark 14 can largely be blamed on this lack of accurate testing. The non-explosive warhead used in testing was more buoyant than an actual warhead, causing the depth issues, and both the magnetic exploder and contact exploder were never tested with a live warhead against a decommissioned ship. Additionally, the gyro steering mechanism, which would later prove problematic and cause circular runs, received little attention during testing. Instead, testing was pushed onto submarine commanders in live warfare situations, revealing technical failures at the worst possible time.

This same lack of pressure-testing caused the aforementioned deficiencies in tactics and difficulties with managing long patrols, contributing to an overall ineffectiveness across the submarine force. In general, the United States went into the war with a misunderstanding of what naval tactics would be employed and where, and technology/industrial production that fell behind its goals at the outset of the fighting. War plans against Japan emphasized a major fleet movement across the Pacific, with a conclusive victory against Japan straight out of the pages of Mahan. Submarines especially suffered from misguided training and objectives, as well as organization that did not contribute to an effective campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, as this possibility was not sufficiently explored before the war. This situation was compounded by economic problems that were largely outside of the Navy’s control, resulting in technology that did not live up to expectations and ultimately resulted in unnecessarily lost submarines and less sunk ships than possible.

These systematic issues were addressed throughout the war, and by V-J Day in 1945, US submarines in the Pacific were a force to be reckoned with, sinking over 4.8 million tons of Japanese shipping from 1943-1945, after sinking merely 725,000 tons in 1941-1942. Warship sinkings also increased dramatically during the war, significantly damaging Japanese naval might by 1944. The effects of this campaign are often understated or misunderstood in popular consciousness, due to the secrecy of submarine operations during and after the war, but after the initial months of ineffectiveness, submarine operations crippled Japanese shipping and significantly contributed to the overall war effort. The mid-war recovery that allowed for this effectiveness can be credited to the flexibility of the US Navy (excluding the Board of Ordinance), the rapid adaptation of US industrial might to wartime production, and the bravery and tactical prowess of countless US submarine commanders and crews. These men, dealt an impossible hand, managed to succeed in the face of all adversity - facing down both the enemy as well as their own command and technology, and never yielding to either.