Finding Karate Again

A Retrospective [Part 1]

Modern American karate is a cargo cult.

Of course, I must qualify this statement: not all dojos are like this, and the art itself is not a problem – but as a whole, the culture and training of karate in the United States has fallen far from its initial stature. Seven-year-olds wear black belts; competition is mostly non-contact or light contact; instructors are physically unfit almost across the board. The art has been commodified, distanced from its roots, and deracinated. To most people, “be careful, that guy does karate” is little more than a punchline.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

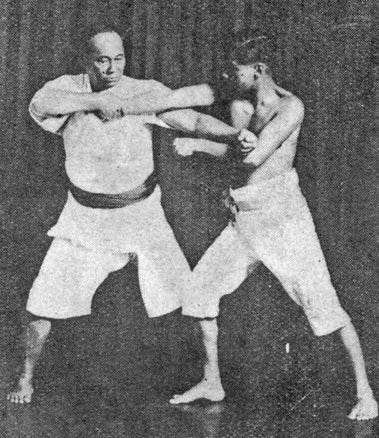

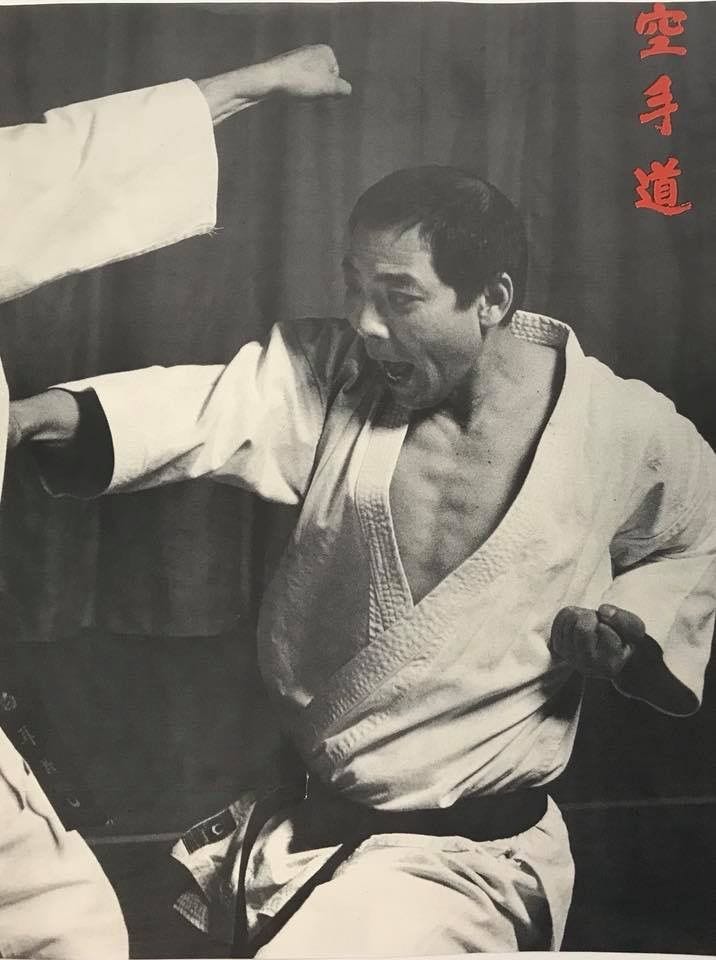

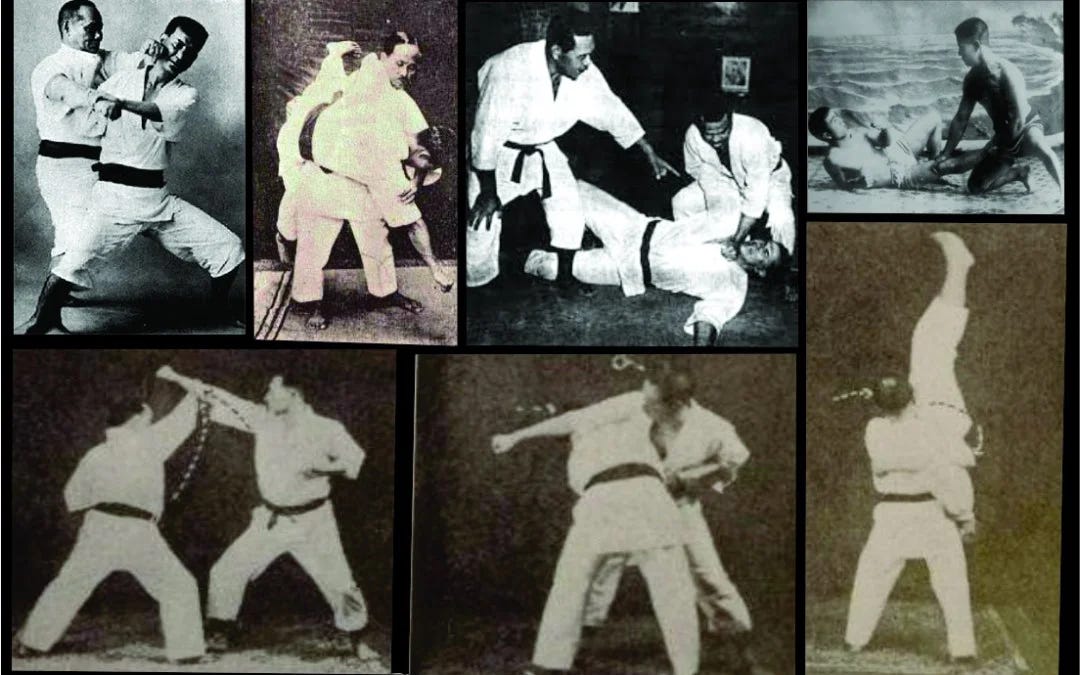

In its older, truer form, karate is one of the most brutal striking arts in the world. I’ll go into more detail on this later, but karate is essentially a formalized bar brawl. Shirts are grabbed, opponents thrown into tables, eyes and throats gouged. A proper karate fight is a bloody, bone-cracking occasion. It’s not snappy kata moves and dainty front kicks – it’s a knock-down, drag-out brawl. This form of karate is unfamiliar to the average practitioner today, but it hasn’t been this way for long, and the art is not “too far gone.”

This older, more muscular form of karate can be revived.

But first, we must understand what happened to that form of karate – that unhewn, feral variety of fighting. This article will attempt to trace the downfall of karate, identify what went wrong, and carve a path for a revival.

ORIGINS

The origin of karate is disputed in seemingly endless ways. Some claim that karate arose out of the need for peasants to effectively take down armored samurai in day-to-day life; others claim that it was an early form of mass wartime training. Still others contend that it was an aristocratic pursuit, a way for samurai to train for war and to induct their children into the world of brutal hand-to-hand conflict.

None of these are quite true, even if they get elements right.

The problem with the history of karate is similar to the problem with the history of Kung Fu – there’s so much regional variety that tracing a single trend is near-impossible, and with multiple Budo bans in Japanese history, the living tradition has been alienated from its ancient origins on multiple occasions.

Either way, it is generally agreed that karate’s earliest origins come from the Ryuku kingdom (specifically Okinawa), and that the early development of the art was influenced by the import of Chinese martial arts to the region. The problem with this etymology is that Japan only annexed the Ryuku kingdom in 1879, and karate in Japan alone traces elements back far further than the late 19th century.

For example: Korean karate (Tang Soo Do in particular) claims its origin as an offshoot of Japanese karate – and its oldest extant text, the Muye Dobo Tongji, was written in 1608, after the Japanese invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597. However, at the same time, Tang Soo Do is named for the Chinese Tang dynasty – further complicating things with the question of Chinese influence.

With this said, karate is by no means a Chinese-imported art; even on a simple visual level, one can see strong stylistic differences between Japanese and Chinese fighting systems. The Chinese arts emphasize circular motions, and placing the weight flightily on the balls and edges of the feet, with sweeping steps. There is also a strong ethos of animal imitation in certain forms of Kung Fu, which is largely absent in karate. We can see elements of Chinese influence in traditional kata, but the art is fundamentally angular rather than circular, as Chinese arts are; the chest is presented to the opponent openly, and the chamber creates a sort of push-pull motion which is extremely different from Chinese martial arts. The weight is placed more centrally on the balls of the feet and the heels, giving a very different feel to training traditional Japanese vs. Chinese forms.

But why am I getting into all of this? Admittedly, I am splitting hairs with the origins of karate here – but it’s important, because it tells us that the origin of karate is more complicated than it is presented.

Clearly, the import of Okinawan karate was folded into an already-extant striking tradition in Japan, influenced by – but separate from – Chinese systems of fighting. And karate became popular not because it was the superior striking system, but because it was the superior training and competition system. Karate was formalized, its techniques were unified, and it was already sportified to a degree (as a form of competition among the Pechin class of Ryuku). There was an already-existent structure of instructors patronized by students, which could be deployed easily in Japan. This structure led to broad popularity as a training method in Japan when teachers came from Okinawa in the late 19th century. It would also lead to the later adoption of karate as a formalized military training method in Japan.

However, at this point, Japan certainly already had striking systems – highly localized, almost familial forms of fighting, both within the samurai class and outside of it. As for the samurai, wrestling was a common form of training from their earliest days, and striking would have been included as an element of fencing. And as for the masses: as an element of swordsmanship, striking and grappling would have been trained in the many competing schools of Musashi’s era, as well as after (with various levels of secrecy).

These striking systems, though poorly-recorded today, would have been more in-line with the mission and philosophy of the samurai – as in, meant for war. They would have been refined by centuries of conflict between daimyo, on top of being influenced by the samurai’s role as a pseudo-law enforcement officer. Unlike the formalized, sportified karate systems that came from Okinawa (mind you, by today’s standards these would still be considered brutal and barbaric), it was these native fighting systems that influenced the regional divergence of karate systems in Japan, further complicated by differences between Okinawan instructors with varying types of Chinese influence on their methods.

Thus, Okinawan karate was juxtaposed onto a martial culture already defined by brutality and variety. The formalization of training in small schools allowed this brutality to be channeled, unified, and sportified for proper competition.

But again, why all of this depth on the early history of karate? Because something is revealed in this complication:

Karate is based on the imposition of structure and technique on an already-brutal “base.”

A fighting populace is a required prerequisite for the complications and abstractions of Okinawan karate to make sense and take hold properly.

Karate is inherently esoteric, meant to be understood by an audience who already speaks the language of unarmed combat.

KARATE ESOTERICISM

This is one aspect of karate that most instructors will insist is not true, but privately admit to believing, without realizing it. Karate is not meant to train “anyone.” Of course, the entire martial arts industry is built on that premise – but it is a faulty one.

Karate is exclusionary by nature, and kata are second-order methods of transmitting physical information. This functions on two levels: reductionist representations of more complex techniques, and muscle memory training.

As for the reductions of more complex techniques, there is no better resource than @karatebreakdown on Instagram. On that account, you can find dozens of videos showing the “strange” techniques of Naihanchi, Bassai, and the Pyung Ahn forms explained with video examples.

Odd footwork and jumping techniques translate to judo-like throws; uncommon “strikes” clearly translate into lapel grabs and manipulation of the opponent’s clothing; out-of-place movements translate to striking from a clinch or hold. If you’ve practiced traditional karate, seeing elements like this come together feels like the black hole scene from Interstellar. I wrote about this here.

The translation of fighting techniques to an individual kata format necessitates these sorts of changes. While they inherently shed some of the information about how to perform the original technique, if properly placed in context they can be a great training aid. The practitioner can mentally run through using techniques in a fight, doing them at full speed against an imagined partner. Obviously, this requires forms to be supplemented with partner drills and sparring, as well as extensive explanation and technical instruction.

Unfortunately, after about two generational cycles of instructors who gradually shifted away from this style of teaching, the original purpose was gradually lost. And yet, the forms remained.

Throws in Bassai became “two-handed punches”; Pyung Ahn E Dan is said to start off with “double blocks”; karatekas endlessly repeat the jump in Jin Do with no clue what or why they’re training.

Cargo-cultism.

A second example of cargo-cultism comes in the other purpose of kata: as a training aid for muscle memory. Karate kata are famously stiff, explosive, and technical, with strict guidelines for how to execute each technique. After the purpose of kata was gradually lost in the public karate mind, the kata in themselves became a guide – “this is how you should fight, explosively and in deep, solid stances.”

Of course, this is ridiculous – and karate is rightfully ridiculed for encouraging this sort of fighting when it does. Point-sparring doesn’t help, when points are scored based on the “technicality” of each strike. While this can help develop good timing and speed, it produces fighters best-described as spazzy. The modern WKF tournament “meta” is the result of forms extrapolated to their logical end. Fighters set up in poised stances, bouncing oddly toward each other, until a flurry of fake-strikes result in flags being raised. This is a method of fighting taken six steps beyond its original intent, extrapolated far past logic.

In reality, the stiffness of kata and line drills is meant as a sort of training aid, rather than a direct representation of how one should fight. In the same way that golfers use swing guides, boxers use speed bags, and baseball players do… whatever this is, kata are meant to improve one’s fighting ability tangentially, rather than indirectly.

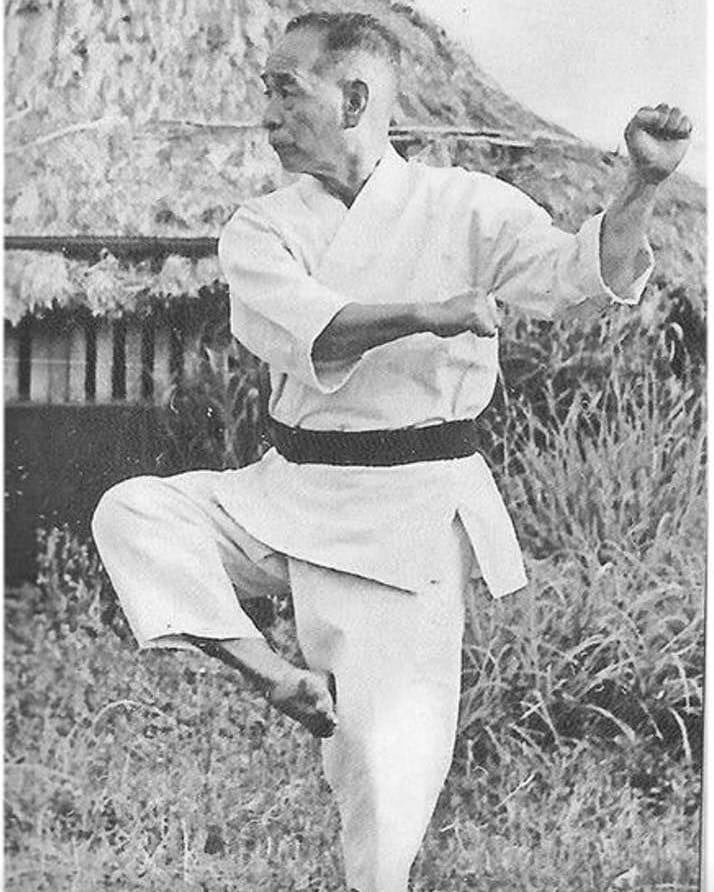

If you’ve met any old karatekas – nowadays in their 70s or 80s – you can see the intended effect of kata training on one’s movement. There’s a looseness to how the old guard of karate practitioners move, which seems to shift dramatically into an indescribable sort of strength when they strike or grip. They don’t hit “hard” – they hit heavy.

This is a direct consequence of “old-school” karate training… because the stiff, technical kata translate to how you should activate your muscles, not the actual way you’re supposed to strike. A front stance is a ludicrous way to throw a cross during a fight – but fundamentally, the muscles you tighten in a front-stanced reverse punch translate perfectly to a boxing-style cross.

Think about it. The front leg steps to the outside and the knee rotates out, but not past the toes. The rear leg drives forward and creates rotational motion, from the ball of the foot, to the calf, to the quads and muscles of the pelvic girdle. The trunk tightens and produces the bulk of the rotational force. The shoulders and arm rotate into the strike for more power. The head stays locked-on to the target, with enough tension in the neck to absorb a slip-and-counter.

Training this very specifically in a kata or line drill is a great way to develop the muscle memory needed for fighting “normally.” It is mental weightlifting as much as it is physical conditioning.

However, this can only make sense to someone who already knows fighting. If you present this without context to someone who has no idea how to fight prior to learning karate, especially if they don’t even have any experience throwing punches, it won’t be interpreted correctly.

Again, we see karate as inherently esoteric; a high-level method of training meant for people who already somewhat know how to engage in violence. If the practitioner is already used to brutality, striking, and grappling, the esoteric elements of karate translate perfectly – however, without that base of instincts, aggression, and body mechanics, it is formless, senseless, inscrutable.

KARATE IN THE WEST

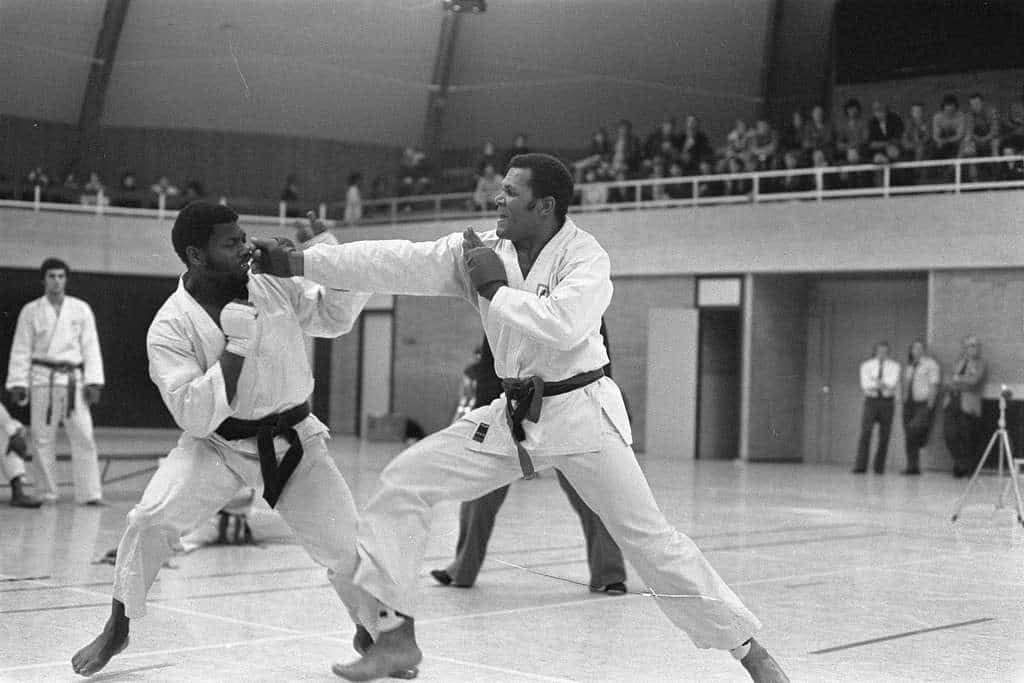

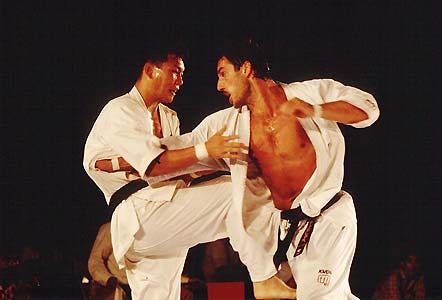

This phenomenon is why the earliest days of Asian martial arts in the United States and United Kingdom produced so many successful fighters and practitioners. The initial trainees in these gyms and groups tended to already be fighters in some sense. Maybe they had trained boxing or wrestling, maybe not – but most had been in fights before at the very least. Karate still had a sort of cultural edge to it, and attracted an audience of young-adult men who wanted to become more skilled at the application of violence – a far cry from the soccer-mom target audience of today.

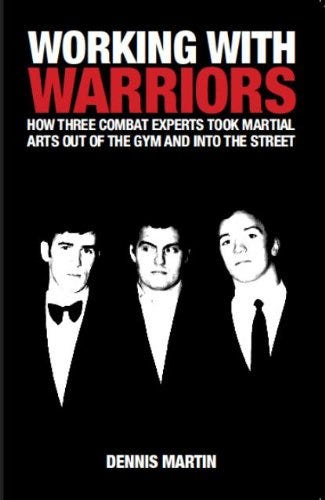

Even those without prior training immediately applied their skills to real-world environments. Consider Dennis Martin, Gary Spiers, and Terry O’Neill in the UK; all of them worked as doormen at sleazy nightclubs, getting into fights regularly. My instructor, and many others of that era did the same, working in high-stakes environments where they’d be very likely to have to depend on their training.

This is why karate in these days seemed to be an almost separate beast from what exists today. The initial cadre of karate trainees in the West was a tough group – and thus, they were able to pick up the nuances of karate’s esotericism. Their ability to transmit this sense of fighting to an increasingly-popular audience varied widely, and degenerated quickly… almost entirely due to the commercialization of Asian martial arts.

The commercialization of karate is something I’ve discussed before, as well as many others. In order to appeal to more students, instructors lowered fitness standards, “lightened” sparring, and made competition increasingly removed from real fighting. After decades of this process, we now have an orc-like degeneration of karate rather than anything like the true fighting system. The target audience of karate classes shifted from adults to teenagers to children to toddlers, and now many dojos make a majority of their revenue from 4-9 year old students.

Competitions shifted to account for this difference, and are now a shadow of what they once were. Below you’ll find some footage from old karate tournaments – a Sabaki Challenge event as well as an unnamed adult tournament. Both are full-contact, bare-knuckle, masculine occasions, with a lot of bravado and blood.

Obviously, things are a bit different now. But I won’t dwell on lamenting the state of karate today.

Instead, I’d like to discuss how it can be restored.

[PART 1 END // PART 2 LATER TODAY]

Reminds of the Katori Shinto-Ryu seated kata, which have these little hops and a hand on the spine of the sword in a few movements. If there’s a reason for it, I don’t know what it is. “Sportification” of the Japanese sword arts have been going on for a long time, but modern kendo is unwatchable, they just wiggle the shinai at each other and make a spazzy lunge at the end.

This reminds me of my experience learning taekwondo. Like a lot of American kids in the 90s, my parents put me and my sister in taekwondo classes. In our case it was taught at a Baptist church by an ex military guy. One day he brought his teacher in to class, a 70 something year old south Korean grandmaster. Watching them spar I instantly realized what we were learning was nothing like what that old man could do. He beat the pants off our instructor all around the room. 20 years younger and he never landed a hit. By the time the demo was over he looked like he was ready to drop. I quit the class pretty soon after that.