This article has also been published on The Dissident Review.

“The fundamental principle underlying all justifications of war, from the point of view of human personality, is ‘heroism’. War, it is said, offers man the opportunity to awaken the hero who sleeps within him. War breaks the routine of comfortable life; by means of its severe ordeals, it offers a transfiguring knowledge of life, life according to death. The moment the individual succeeds in living as a hero, even if it is the final moment of his earthly life, weighs infinitely more on the scale of values than a protracted existence spent consuming monotonously among the trivialities of cities. From a spiritual point of view, these possibilities make up for the negative and destructive tendencies of war, which are one-sidedly and tendentiously highlighted by pacifist materialism. War makes one realize the relativity of human life and therefore also a law of ‘more-than-life’, and thus war has always an anti-materialist value, a spiritual value.”

–Julius Evola, Metaphysics of War

There has always been something spiritual about warfare. It is greater-than-human; a supernatural struggle intertwined with the brutal reality of fatal clashes. In Evola’s words, it is an opportunity to awaken the hero within.

Today, with vast changes in warfighting and the rise of pacifist materialism, this notion has fallen out of favor. However, the spiritual aspect of war is an innate human truth, and has been accepted to the point of religious integration by every fighting society since the Stone Age. As long as man has gone to war, he has elevated it beyond a mere struggle of flesh and steel. Further, warriors have always elevated themselves beyond the physical, through ritual, belief, and philosophy. A man with a sword and a shield is just a man, but a man imbued with divine fury is something greater, more formidable.

However, there exists a longstanding dichotomy in how fighting cultures have “elevated” their warriors: the pagan vs. the Christian view. This dichotomy can be viewed as the classical contrast between Apollonian and Dionysian thought, yet simply ascribing it to that debate doesn’t fully do it justice. There’s more to be investigated here.

In general, the different schools of thought can be described as such:

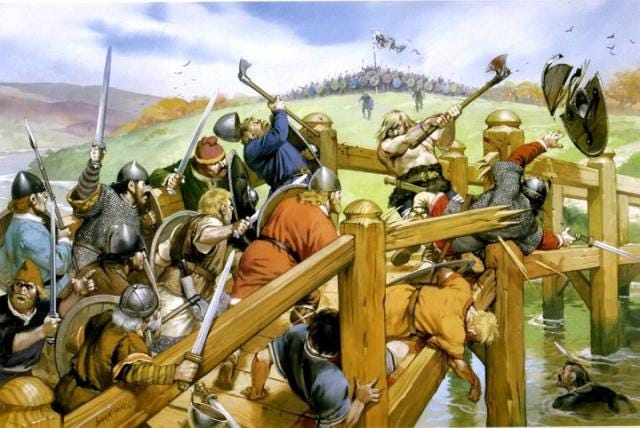

Pagan (i.e. Viking berserkers): Immediately before battle, warriors would ritually “rewild” themselves, shedding their humanity and therefore their human weaknesses. They aimed to embody the strength of a bear or the speed of a wolf, and fight with superhuman ability.

Christian (i.e. Knights Templar): These warriors aimed to live in a way that brought them closer to God, so they can act as extensions of divine will. Through sacraments and a strict lifestyle, they aimed to embody pious virtue, and they succeeded on the battlefield because no opposing force could stop the hand of God.

These ethoses are vastly different, yet aim to achieve the same goal. In the pre-firearm era moreso than today, individual bravery in combat could change the outcome of an entire battle. So, these religious concepts of “elevating” warriors aimed to create unstoppable fighters who would not hesitate or flee, warriors who could fight through any pain or fear. For example: Viking berserkers were said not to bleed when cut, and Crusader armies regularly routed forces five or six times larger. Clearly, this notion of elevating warriors beyond mere human flesh and bones worked.

But let us delve into the individual philosophies at play here.

The pagan warrior ethos, best represented by Viking berserkers or Proto-Indo-European Kóryos, is one that feels instantly familiar, almost evolutionarily built-in. Anyone can imagine the act of shedding their human woes, their social conditioning, their conscious and subconscious humanity. Reverting to something older, something wilder. It’s a matter of simply un-learning that which has been learned; walking back through the stages of evolution. You can imagine it now: biting at your shield, snarling. Nearly naked, yet unfazed by the winter cold. But there’s much more to berserking than simply deciding to “go berserk”. I wrote an article which details the rituals and ideas behind berserkers, though I’ll recap here:

Berserkers spent days or weeks in the wild prior to battle, living alone and surviving by their own labor. Rituals, songs, and dances were then used to induce a state of frenzy. Henbane – a psychotropic plant – was likely ingested, which lowered blood pressure, probably contributing to accounts of invulnerability. The result was a warrior with no fear and no hesitation, who did not feel pain. Even other Vikings feared facing berserkers in combat, and accounts of these warriors cutting through enemy lines without injury are numerous.

In a way, berserkers were “shifting down” – reducing their humanity to something animalistic and wild. In that state, they were wolves and bears, not people. Some historians and psychologists postulate that this was undertaken to distance themselves from their acts of violence, though this is a shaky proposition based on a hyper-modern moral framework. Humanity’s familiarity and comfort with violence has drastically dropped in recent decades, and to assume that our ancestors had such reservations about violence is a faulty premise. These were men who lived and died by the sword; they were as comfortable with combat as we are with eating breakfast. To ascribe modern morals to them is to misjudge their priorities.

In fact, when one considers all of human history, pillaging is the oldest profession. The fact that we aren’t constantly pillaging each other today is a testament to modern civilization’s perseverance and ubiquity.

But I digress. These men did not go berserk to distance themselves from violence; if they did, the complex rituals surrounding berserking would never have existed. Rather, to go berserk was to induce an altered state of consciousness, with the explicit goal of becoming more effective in combat.

The most important aspect, constantly reiterated in primary sources, is the fearlessness of berserkers. In the sagas and in outside accounts of Viking rage, that word comes up over and over again. They acted without hesitation. They charged forward without a single reservation. They did not think; they simply fought with an almost inhuman fury.

This was the pagan warrior ethos.

To fight like an animal, who never second-guesses his actions. To adopt the strength of a bear, because one isn’t holding back even an ounce of power. To move with the speed of a wolf, because one isn’t hampered by being tired or scared.

The aim was to achieve superhuman feats of combat by simply unshackling a warrior from his human nature. They were “shifting down” from the typical plane of human existence, but with the intention of being able to achieve more. To become superhuman in the literal sense of the word: stronger, faster, more durable.

Compare this with the Christian warrior ethos, which is opposite in almost every way, yet aimed at achieving the same goal. This philosophy is best exemplified in the code of the Knights Templar, papal guidance for Crusaders, and knightly codes of chivalry; the general picture that arises from these sources is a warrior ethos diametrically opposed to pagan animalism. First, some background:

The Crusades were framed as a worldly extension of God’s will, and to take the cross was to resign oneself to following God’s will above one’s own. To die on a crusade was to die in service of God himself, and to be absolved of sin.

But this notion did not simply lead to suicidal tactics. Despite the overall outcome of the Crusades, crusaders were extremely successful on the tactical level; their casualty ratios were very favorable in almost every engagement. Of course, their supply lines were eventually attacked and cut, but in terms of actual combat, Templars and other crusading knights were utterly dominant. They fought valorously and fearlessly, often causing much larger forces to flee in fear. This wasn’t simple piety and conviction in one’s purpose. It ran deeper, religiously and psychologically.

The core of the Christian warrior ethos is, unlike the pagan ideal, to “shift up”. Templars, through their oath of poverty, chastity, and obedience, aimed to bring themselves as close to God as possible, so they may enforce his will without hesitation or fear, even of death.

They did this through an extremely strict lifestyle, forgoing worldly pleasures. The code of the Knights Templar included prohibitions on sex, expressions of wealth, clothing other than a plain tunic, pastimes such as falconry, and more. They attended mass daily. The goal was to live in the best imitation of Jesus’ disciples as possible: reserved, poor, and pious.

All of this served to make the Templars embody virtue. They aimed to be so in-touch with God, and so removed from worldliness, that their every action was only as God intended. In a sense, it was religious transhumanism: becoming better than human by embodying God’s will and God’s will alone. “Warriors of light” is a common phrase attached to crusaders, for this exact reason.

Psychologically, the aim of all of this was to create absolute conviction and confidence in a knight’s every action. Is this not the same goal as the Viking berserker, who, in his reversion to animal behavior, never second-guesses any act? The Christian warrior ethos aimed to cultivate this unshakeable confidence – which extends to fearlessness in combat – by emphasizing one’s embodiment of virtue. To some extent, the Christian philosophy was more ambitious; berserking only required a short period of absolute fearless confidence, while the Christian view aimed to make this confidence constant.

Either way, they served the same purpose: making warriors utterly unstoppable on the battlefield, by removing all reservations or hesitation.

The berserker was unafraid of death in the same manner that a bear is unafraid of death. His conviction comes from lack of human thought, a return to animalistic impulse.

Conversely, the Christian warrior is unafraid of death because he knows that dying in service of God means absolution of his sins and eternal glory. His conviction in combat comes from the conviction that he is embodying The Light. He is virtue; he is a manifestation of God’s will. Every stroke of the crusader’s sword is a religious act; every charge is protected by divine will.

The dichotomy here is endlessly fascinating. Both ideologies in some way conceptualize man as a fusion of beast and spirit, or rather divinity. Their warrior philosophies simply take opposite directions. Pagan warrior rituals shift a man toward his beastly side, while Christian warrior rites aim to bring a man closer to divinity.

Some have suggested that the pagan ethos evolved into that of the Christian knight, or that they are both divergent from the Proto-Indo-European Kóryos way of life. Either of these hypotheses could very well be true.

However, my interest lies in discovering why both were extremely effective.

END PART I

Part II will examine these practices in the context of psychology, as well as reflections on the citizen-soldier archetype seen in Ancient Greece, which seems to involve a different mindset than either presented here. If you have any thoughts or questions, feel free to comment.

Selected Sources & Further Reading

Stark, Rodney. God’s Battalions: The Case for the Crusades.

Saunders, Frances Stonor. The Devil’s Broker: Seeking Gold, God, and Glory in Fourteenth-Century Italy.

Evola, Julius. Metaphysics of War.

Jones, Dan. Templars: The Rise and Spectacular Fall of God’s Holy Warriors.

Price, Neil S. The Viking Way: Magic and Mind in Late Iron Age Scandinavia.

Price, Neil S. Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings.